TDM 40200: Project 5 - Introduction to MLOps - Extended

Project Objectives

Last week we covered some of the basics of MLOps (Machine Learning DevOps) like repository structure, modularizing functions, importing using Python modules, setting up an API to serve predictions and global configuration files! This week we are going to expand on our pipeline using tools like Pydantic, MLFlow, and Pytorch Lighting.

Dataset

-

/anvil/projects/tdm/data/wine/wine_quality_type.csv

|

If AI is used in any cases, such as for debugging, research, etc., we now require that you submit a link to the entire chat history. For example, if you used ChatGPT, there is an “Share” option in the conversation sidebar. Click on “Create Link” and please add the shareable link as a part of your citation. The project template in the Examples Book now has a “Link to AI Chat History” section; please have this included in all your projects. If you did not use any AI tools, you may write “None”. We allow using AI for learning purposes; however, all submitted materials (code, comments, and explanations) must all be your own work and in your own words. No content or ideas should be directly applied or copy pasted to your projects. Please refer to the-examples-book.com/projects/spring2026/syllabus#guidance-on-generative-ai. Failing to follow these guidelines is considered as academic dishonesty. |

Questions

Question 1 (2 points)

Clean Model Training - PyTorch Lightning

Last project we made it a point to organize our methods into their own files like for data loading and for training, etc. This is pretty standard, and because of what we did last project, the conversion to another great method will be very simple. One of the most important things, especially as projects grow, is encapsulation. It reduces risks and confusion, separates concerns, etc.

We are going to introduce PyTorch Lighting which can help with this. It does not necessarily abstract all your code but it helps organize your model instantiation, training loops, hyperparameters and more in a very intuitive object oriented way.

First, lets get our directory structure in order. Please create a new directory called intro_mlops_2/ at the root of your project with all the files we had from last project in it. Then move your notebook into the intro_mlops_2/notebooks/ directory. We are then going to add a __init__.py file to the intro_mlops_2/ directory to make it a package. This way we can keep all our files organized and separate from the previous project and import them properly:

intro_mlops_2/ ├── __init__.py # ADD THIS ├── notebooks/ # move your notebook here │ └── your_notebook.ipynb ├── src/ │ ├── __init__.py │ └── ... └── ...

|

To ensure the imports work properly, you need to run the commands in the terminal from just outside of the |

Now, we will focus on creating a LightningModule for our current PyTorch model - with this we can define some standard operations and more easily scale our operation.

Please create a new file called lightning.py in the src/ directory.

Here, we are going to create a class that inherits from pl.LightningModule and then we will define our model, loss function, and optimizer. We will also define a much simpler looking training loop.

# src/lightning.py

import pytorch_lightning as pl

import torch

from torch import nn

class WineQualityClassifier(pl.LightningModule):

def __init__(self, model, learning_rate, epochs):

super().__init__()

self.save_hyperparameters(ignore=["model"]) # don't serialize the model object

self.model = model

self.loss_fn = nn.CrossEntropyLoss() # cross entropy loss is a common loss function for classification tasks

...|

We are going to use a slightly more complex dataset for this project compared to the previous one. This dataset has more features and more classes to predict, more detail can be found at Wine Quality Dataset Kaggle page. |

Here we define how our model class will be initialized. It inherits pl.LightningModule which allows our instantiation to make use of the parent class’s functions, attributes, features, etc. (the parent class being pl.LightningModule).

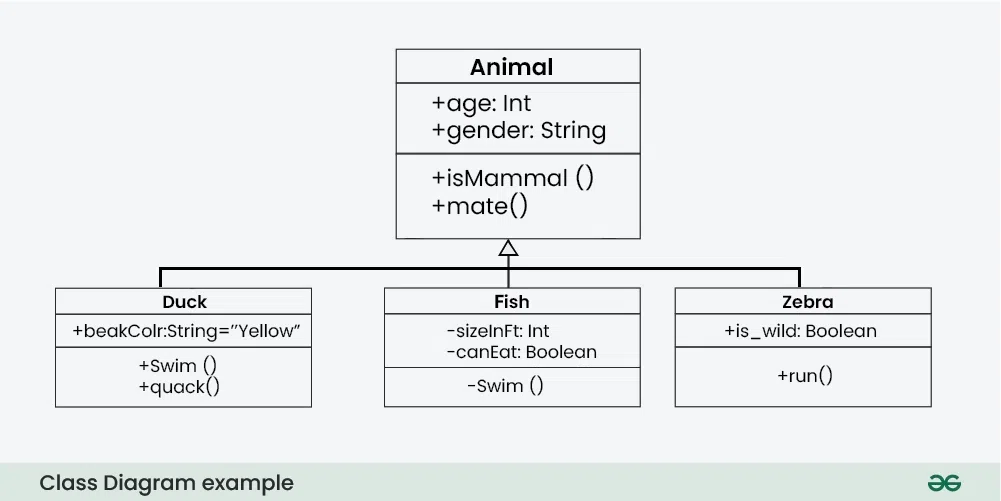

If that is a little hazy, take this for example:

Here we see Duck, Fish and Zebra. They are all animals and fundamentally have a set of similar attributes, so you can create a parent class with a minimum set of attributes that all animals have and then have each animal inherit from it. This way you can ensure some baseline functionality for all animals like age, gender, +isMammal(), etc. They can also each have their own unique features like +swim(), +fly(), +run(), etc.

Also, parent classes will sometimes leave functions blank and expect you to fill them in i.e. all animals mate but they do not all have the same mating behavior, hence you may need to override it when creating a Duck vs creating a Fish.

In our case, WineQualityClassifier (Duck, Fish, Zebra etc.) inherits from pl.LightningModule (Animal) and inherits the features and attributes of the parent class like forward, training_step, configure_optimizers, etc. It can also have its own unique features like model, loss_fn, etc.

But remember how we already created a model class in the previous project? We can use that here to pass in as a parameter to our WineQualityClassifier class. This way we can make our lightning module more flexible and reusable.

# src/lightning.py

class WineQualityClassifier(pl.LightningModule):

def __init__(self, model, learning_rate, epochs):

super().__init__()

self.save_hyperparameters(ignore=["model"]) # don't serialize the model object, isnt a hyperparameter

self.model = model

self.loss_fn = nn.CrossEntropyLoss()Moving on, we can then define other key methods we will want in our model class:

# src/lightning.py

class WineQualityClassifier(pl.LightningModule):

...

def forward(self, x):

return self.model(x)

def training_step(self, batch, batch_idx):

x, y = batch # splits out data (`x`) and labels (`y`)

logits = self(x) # passes data into models forward method

loss = self.loss_fn(logits, y) # calcs loss based on logits (output of model) and ground truth

self.log("train_loss", loss) # this is a special method that logs the loss at each step

return loss

def configure_optimizers(self):

# uses self.hparams

return torch.optim.Adam(self.parameters(), lr=self.hparams.learning_rate)All three of these are keyword functions we need to implement in our subclass since these are core to the function of our model:

-

forward()simply passes the data your models own method to kick off training. -

training_stepis a much more conveniently structured training loop that is called when you run thepl.Trainerwhich we will touch on later.-

We will get into the

batchin the next question when we define a dataloader.

-

-

configure_optimizerssimply defines which optimizer we are using and passes in the parameters we want to set for it.

|

The |

By defining these methods in the LightningModule class, they are automatically called when the model is trained and validated.

If you noticed from last project, we did not define a validation step, only a training and test step, but here we can easily add one by defining a validation_step method. This will also be automatically run during training time.

Note that validation is used to fine tune hyperparameters and assess current performance but is not actually trained on.

# src/lightning.py

class WineQualityClassifier(pl.LightningModule):

...

def validation_step(self, batch, batch_idx):

x, y = batch # splits out data (`x`) and labels (`y`)

logits = self(x) # passes data into models forward method

loss = self.loss_fn(logits, y) # calcs loss based on logits (output of model) and ground truth

preds = logits.argmax(dim=1) # predicted class per sample

acc = (preds == y).float().mean() # fraction correct

self.log("val_loss", loss)

self.log("val_accuracy", acc) # so you can see accuracy in results and in callbacks

return lossComparing with last project, the overall steps are very similar but instead we use the pl.LightningModule class to help us organize our logic. It is much easier and cleaner to define the steps for your model using this method. It will also remove the need to define the training loops like we have in src/trainer.py since we have it all within the one class. Nice and convenient!

Now that we have defined our custom model using LightningModule, we can import it in the main.py file just like how we did with the previous project’s model:

# main.py

from intro_mlops_2.src.lightning import WineQualityClassifier

import pytorch_lightning as pl

...

simple_nn = SimpleNN(INPUT_SIZE, NUM_CLASSES)

model = WineQualityClassifier(simple_nn, learning_rate=0.001, epochs=5)

# don’t need these anymore since they are methods within the LightningModule class!

# criterion = nn.CrossEntropyLoss()

# optimizer = optim.Adam(model.parameters(), lr=LEARNING_RATE)Note that in the current state, our pipeline in main.py will not work properly without some modification. Since we are using this approach, the training for our model relies on a slightly different form of the dataloader which we will touch on in the next question. We will also work on integrating everything in Question 4.

1.1 Two-three sentences explaining the general flow and benefits of this setup.

1.2 Run !cat {your_path_to_project}/intro_mlops_2/src/lightning.py.

Question 2 (2 points)

Setting up a Dataloader

Last project we had this setup:

# main.py - project 4

# process data

X, y, label_encoder = load_and_preprocess_data(DATA_PATH / 'data.csv')

# test train split

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = split_data(X, y, train_ratio=TRAIN_SPLIT)

# make loaders

train_loader = create_data_loaders(X_train, y_train, batch_size=BATCH_SIZE)It is already fairly clean and makes use of the helper functions we defined last time, but these steps are pretty much the same everywhere so there is no reason to have them in our main logic. We already create a dataloader here in our helper functions:

# src/data_loader.py - project 4

def load_and_preprocess_data(data_path):

"""Load and preprocess the dataset"""

...

def split_data(X, y, train_ratio=0.8):

"""Split data into train and test sets"""

...

def create_data_loaders(X_train, y_train, batch_size=32):

"""Create PyTorch data loaders"""

train_dataset = TensorDataset(X_train, y_train)

train_loader = DataLoader(train_dataset, batch_size=32, shuffle=True)

return train_loaderBut instead of having multiple helper functions in our main logic to eventually get to a dataloader, we can use the datamodule provided by Lightning instead - LightningDataModule. We once again create a custom class that inherits from a module and implements the relevant functions. This encapsulates a lot of the core boiler plate repeated logic into a nice class.

Open up data_loader.py and we will essentially just wrap these functions we already created into the DataModule object. Since we are using a LightningDataModule, we need to implement the following methods:

-

setup(self, stage=None): Load and preprocess the data -

train_dataloader(self): Return the training data loader -

val_dataloader(self): Return the validation data loader

# src/data_loader.py - project 5 version

import pytorch_lightning as pl

class WineQualityDataModule(pl.LightningDataModule):

def __init__(self, data_path, batch_size=32, train_split=0.8): # you can add more parameters here if you want

super().__init__()

self.data_path = data_path

self.batch_size = batch_size

self.train_split = train_split

def setup(self, stage=None):

"""Load and preprocess the data"""

...

def train_dataloader(self):

"""Return the training data loader"""

...

def val_dataloader(self):

"""Return the validation data loader"""

...However we first need to quickly talk about the data we are using. This dataset consists of 11 features and 1 target label column quality. In your notebook, under the intro_mlops_2/notebooks/ directory, please load the data and print the first few rows to see what it looks like.

import pandas as pd

data = pd.read_csv('/anvil/projects/tdm/data/wine/wine_quality_type.csv')

print(data.head())We see there is a column called type which is either Red or White but we want to predict the quality of the wine based on the other features, so we will drop the type column.

So we just need to make a slight modification to how we obtain our X and y variables in our setup method.

# src/data_loader.py

import pytorch_lightning as pl

class WineQualityDataModule(pl.LightningDataModule):

...

def setup(self, stage=None):

# Load and preprocess data - same logic from load_and_preprocess_data()

data = pd.read_csv(self.data_path).dropna()

X = data.iloc[:, :-2].to_numpy() # gets features - ignores `type`

y = data.iloc[:, -2].to_numpy() # gets the target label

# Normalize features

...

# Encode labels

...

# Split data - same logic from split_data()

...

# Convert to tensors - saving these in self so we can use them in our dataloaders

self.train_dataset = TensorDataset(torch.FloatTensor(X_train), torch.LongTensor(y_train))

self.val_dataset = TensorDataset(torch.FloatTensor(X_val), torch.LongTensor(y_val))Please fill in the … with the appropriate code (which is the same logic from our helper functions in the previous project) but this time please use the attributes we defined in the init method when encoding and splitting the data (i.e. self.data_path, self.batch_size, self.train_split)

|

Our |

Since our logic is now encapsulated, you can delete those helper functions we created last time.

Before we move on, we are going to add a quick data transformation into our datamodule to our target labels. Originally, the quality is rated between 0 to 10 which is a lot classes and the rating is somewhat subjective, so how can our model accurately differentiate between a 6 and a 7? To get around this, we are going to 'bin' the quality scores into 3 categories. This way, its less granular and more manageable for our model leading to some more interpretable results.

Please modify the setup method to include this:

# src/data_loader.py

class WineQualityDataModule(pl.LightningDataModule):

def setup(self, stage=None):

# Load data

data = pd.read_csv(self.data_path)

# Create quality bins

def bin_quality(quality):

if quality <= 4:

return 0 # Bad

elif quality <= 7:

return 1 # Mid

else:

return 2 # Good

# Apply binning

data['quality_binned'] = data['quality'].apply(bin_quality)

# Features and target

X = data.drop(['quality', 'quality_binned', 'type'], axis=1).values # .values converts the dataframe to a numpy array

y = data['quality_binned'].values

# Rest of preprocessing...|

Here we precompute some simple data transformations to make our data more manageable. If you are however working with some more complex data transformations like stochastic transformations (e.g. augmentation) or you want them to be parallelized by DataLoader workers then you should look at an 'online' transformation method. A quick example shown here: By performing the transformation in the |

Now that we have our datamodule class setup, we can remove those helper function calls we have in our main.py file since we have it all encapsulated in our LightningDataModule class. There now remains only one thing to do before we can test our pipeline!

If you remember last project we decided to create those helper functions like train_one_epoch to hide the nitty gritty details like zero the gradient. We can use the Trainer method from PyTorchLightning to do all that, but even cleaner. Our main.py should now look like this:

# main.py

from intro_mlops_2.src.lightning import WineQualityClassifier

from intro_mlops_2.src.data_loader import WineQualityDataModule

...

# Initialize model and dataloader

simple_nn = SimpleNN(INPUT_SIZE, NUM_CLASSES)

model = WineQualityClassifier(simple_nn, learning_rate=LEARNING_RATE, epochs=EPOCHS)

datamodule = WineQualityDataModule(data_path=DATA_PATH / "wine_quality_type.csv", batch_size=BATCH_SIZE)

# Initialize trainer object and train

trainer = pl.Trainer(max_epochs=model.hparams.epochs)

trainer.fit(model, datamodule=datamodule)|

Please change the DATA_PATH and EPOCHS variables in your |

It abstracts all those annoying little details and makes use of your simple training_step in your LightningModule class to perform training to your specifications. It also has a bunch of different parameters you can pass into it to customize your training - we will touch on a couple later.

2.1 Run !cat {path}/intro_mlops_2/src/data_loader.py | head -n 45.

2.2 Run !cat {path}/intro_mlops_2/main.py.

2.3 Run the pipline (in the notebook under the intro_mlops_2/notebooks/ directory): !cd ../../; python -m intro_mlops_2.main.

Question 3 (2 points)

Validate Model Config Files

Nice! Now we have a pretty sick streamlined training setup. But, we have all those model and training parameters we are specifying when instantiating our classifiers and datamodules, we can use a different approach to manage them. We put everything into the config.py last time - path variables, model parameters, etc. We are going to move those model parameters into a YAML file called model.yaml. YAML files are similar to JSON in the sense they allow us to create a more readable and structured format for our configurations. We will also do a quick intro to a commonly used library called Pydantic which helps us validate schemas - this is to just make sure we are not attempting to load malformed data into our model.

Since we are creating more and more configuration type files, why do not we first create a new directory called configs/ at the root level (at the same level as src, notebooks etc.). Move config.py into it and then create a model.yaml file in that directory.

The new file structure should resemble this:

intro_mlops_2/ ├── __init__.py ├── notebooks/ │ └── firstname_lastname_project5.ipynb ├── configs/ │ ├── model.yaml │ ├── __init__.py │ └── ... ├── src/ │ ├── __init__.py │ └── ... └── ...

This is the same information we had in our config.py (changed the EPOCHS variable to 5 for faster training), but in YAML format - it is very similar to JSON if you are familiar and is very often used for specifying configs.

# configs/model.yaml

training:

train_split: 0.8

batch_size: 32

learning_rate: 0.001

epochs: 5 # less epochs for faster training

model:

input_size: 11

num_classes: 3 # multi-class

# typically would have more params like dropout rate, or number of hidden layers but for simplicityOkay, so we now have a new streamlined training setup, a new config directory and we have moved our configurations for our model into a new YAML file. Now, we want to actually use the configurations we specified in our YAML file which in it of itself is very simple and can be done like so:

import yaml

with open(path, "r") as f:

config_dict = yaml.safe_load(f)But note that this does not check the formatting of our YAML. What if there is some malformed configuration or a malicious configuration? We can enforce some safety using a library called Pydantic.

So in a new file called validation.py under our configs directory, we are going to use Pydantic to define schemas for how our data should look. Pydantic does this by using Python classes with specified attributes and datatypes (more examples in their docs).

Here is an example of how we can define a schema for our training and model configurations:

# configs/validation.py

import yaml

from pydantic import BaseModel

# define the schemas for our training and model configurations

class TrainingConfig(BaseModel):

train_split: float

batch_size: int

learning_rate: float

epochs: int

class ModelConfig(BaseModel):

input_size: int

num_classes: int

# To simplify our definitions we can create a single class that have definitions from both TrainingConfig and ModelConfig - has its benefits but is not always necessary to do it this way

class FullConfig(BaseModel):

training: TrainingConfig

model: ModelConfig

# this function will load the YAML file and run a schema check on the loaded yaml

def load_config(path: str) -> FullConfig:

with open(path, "r") as f:

config_dict = yaml.safe_load(f)

return FullConfig(**config_dict) # this performs the validationThis creates a class for the training and model parameters which contain their respective attributes and datatypes. When a single class uses both of these as types for the training and model attributes, those attributes should be defined in the configuration file. The load_config() returns you an object that contains all the parameters needed. This is good because you can experiment with different model and training parameters and just need to change the file paths being loaded in!

|

We can also do some tricks with our YAML file to add multiple configurations for our model and training parameters and have our Pydantic schema validate all of them so we can perform different experiments with different configurations. Here is a quick (not mandatory) example of how we can do this: And then we need to modify our Pydantic schemas to handle the new experiments configuration and then change how we reference the config after loading it: Finally, after its loaded, we can access the experiments like so: We are not going to use this in our project, but it is a nice way to manage multiple configurations and experiment with different parameters. |

This is very nicely abstracted so now wherever we need to get our model parameters, we can load them in like so:

from intro_mlops_2.configs.validation import load_config

config = load_config("configs/model.yaml")

print(config)So now, in main.py we could replace all references to things like TRAIN_SPLIT with

config["training"]["train_split"]But we can take this one step further…

Instead of passing every training parameter through main.py, we can use a pretty slick feature of class inheritance to load config values behind the scenes for both WineQualityClassifier and WineQualityDataModule.

We are going to add a function to both called from_config_path with a special decorator @classmethod (more info can be found at classmethod(), Python document). The datamodule version takes config_path and data_path, while the classifier version takes model and config_path.

We will call the `load_config() function in both files (meaning you need import it there, too), and return an instance of the class:

# src/data_loader.py

from intro_mlops_2.configs.validation import load_config

class WineQualityDataModule(pl.LightningDataModule):

def __init__(self, data_path, batch_size, train_split):

super().__init__()

self.data_path = data_path

self.batch_size = batch_size

self.train_split = train_split

...

@classmethod

def from_config_path(cls, config_path, data_path):

config = load_config(config_path)

return cls(

data_path=data_path,

batch_size=config.training.batch_size,

train_split=config.training.train_split

)# src/lightning.py

from intro_mlops_2.configs.validation import load_config

class WineQualityClassifier(pl.LightningModule):

def __init__(self, model, learning_rate, epochs):

super().__init__()

self.save_hyperparameters(ignore=["model"])

self.model = model

self.loss_fn = nn.CrossEntropyLoss()

...

@classmethod

def from_config_path(cls, model_cls: nn.Module, config_path: str):

config = load_config(config_path)

model = model_cls( # instantiate the model with the input size and number of classes from the config

input_size=config.model.input_size,

num_classes=config.model.num_classes,

)

return cls( # return the class with the model, learning rate, and epochs from the config

model=model,

learning_rate=config.training.learning_rate,

epochs=config.training.epochs,

)This way we can pull training parameters from YAML while still passing the instantiated neural network into the classifier, which keeps the model definition and Lightning training logic cleanly separated.

Inside your notebook, please try loading the configs successfully and then changing a value in the model.yaml that would break and see the output:

# notebooks/your_notebook.ipynb

import sys

from pathlib import Path

sys.path.append(str(Path("../..").resolve()))

from intro_mlops_2.configs.validation import load_config

from pathlib import Path

path = Path("~/project-04/intro_mlops_2/configs/model.yaml").expanduser()

config = load_config(path)

print(config)

print("training: ", config.training)

print("model: ", config.model)3.1 Run print_directory_tree to show the new changes.

3.2 Load the configs successfully in your notebook.

3.3 Change a value in the model.yaml that would break and see the output.

Question 4 (2 points)

Integrating Everything

Now let’s integrate everything we have built!

Alot of the work is now performed in the classes themselves and in the from_config_path methods which validates the configurations for us and then instantiates the classes. This way we can update our main.py to a much cleaner look:

# main.py

import pytorch_lightning as pl

from intro_mlops_2.configs.config import *

from intro_mlops_2.src.data_loader import WineQualityDataModule

from intro_mlops_2.src.lightning import WineQualityClassifier

from intro_mlops_2.src.neural_net import SimpleNN

# Create model and datamodule from config

model = WineQualityClassifier.from_config_path(SimpleNN, CONFIG_PATH / "model.yaml")

datamodule = WineQualityDataModule.from_config_path(CONFIG_PATH / "model.yaml", DATA_PATH / "wine_quality_type.csv")Lets run our new pipeline! First though, we should comment out the old code to graph and save model weights since we are not using them anymore. However, we still need to save the label encoder so we can use it when serving the model, please go into the src/data_loader.py file and add the following code to the end of the setup() function:

# src/data_loader.py

import pickle

from intro_mlops_2.configs.config import MODEL_PATH

...

def setup(self, stage: str):

...

# Save the label encoder

with open(MODEL_PATH / "label_encoder.pkl", "wb") as f:

pickle.dump(self.label_encoder, f)Now we should be able to run our new pipeline! Quick check, our main.py should now look like this:

# main.py

... # the other imports

from intro_mlops_2.configs.config import *

from intro_mlops_2.src.data_loader import WineQualityDataModule

from intro_mlops_2.src.lightning import WineQualityClassifier

from intro_mlops_2.src.neural_net import SimpleNN

... # the seeds being set, model initialization and datamodule initialization

# Initialize trainer and train

trainer = pl.Trainer(max_epochs=model.hparams.epochs) # notice the hparams.epochs is being used to set the max number of epochs based on the models config

trainer.fit(model, datamodule=datamodule)

# Validate the model (output includes val_loss and val_accuracy)

val_results = trainer.validate(model, datamodule=datamodule)

print("Validation results:", val_results)

# remove all the code to graph and save model weights since we are not using them anymore.In your notebook, please run this code to see the validation results:

# notebooks/your_notebook.ipynb

!cd ../../; python -m intro_mlops_2.mainThe output looks a little cluttered because of all the CUDA / TensorFlow warnings about not running in a GPU environment printed at startup but you can safely ignore them.

Also note that in the same directory level as intro_mlops_2 you should see a new directory called lightning_logs/ with a subdirectory called version_X/ containing the training logs.

Each version contains a events.out.tfevents file which is the training log. You can normally view the training logs by using something like TensorBoard but it will not quite work in Anvil so we will look at a different way to view the logs. Each version folder also contains a hparams.yaml file which contains the hyperparameters used for that version of the training as well as a checkpoints/ folder which contains the checkpoint files for that version of the training. For now, please just run this command to show your lightning logs:

# notebooks/your_notebook.ipynb

root_path = "~/project-04/lightning_logs" # adjust as needed

print_directory_tree(root_path, max_depth=3)Adding Callbacks for Better Training

Now let’s enhance our training with some useful callbacks.

In PyTorch Lightning, a callback is a small piece of logic that "hooks into" the training process at the right time (end of an epoch, after validation, when saving checkpoints, etc.). Instead of writing extra if statements and bookkeeping code in your training loop, you instantiate a callback object and attach it to the Trainer object which then runs the callbacks for you at the appropriate times!

Callbacks are definitely worth learning because they are one of the most common ways to make training:

- safer → avoid overfitting / wasted compute

- more reproducible → automatically save the best model

- more scalable → easy to add more behaviors later without rewriting your model code

EarlyStopping Callback

The first callback we will create is EarlyStopping. This prevents your model from overfitting by automatically stopping training when the validation loss stops improving. Without this, you might train for all 50 epochs even if the model stopped getting better at epoch 30 - wasting compute time and potentially making the model worse.

# main.py

from pytorch_lightning.callbacks import EarlyStopping

...

# model/dataloader instantiation

# callbacks are instantiated here

early_stopping = EarlyStopping(

monitor="val_loss", # which metric to watch

patience=10, # how many epochs to wait before stopping

mode="min" # stop when val_loss stops decreasing

)

# the callbacks are then attached to the trainer objectThe patience parameter means "wait 10 epochs without improvement before stopping". So if validation loss stops improving at epoch 20, training will continue until epoch 30 to make sure it is really stuck, then stop automatically.

ModelCheckpoint Callback

The second callback is ModelCheckpoint, which automatically saves your best model during training. This is crucial because you want to keep the model from the epoch that performed best on validation data, not necessarily the final epoch.

# main.py

from pytorch_lightning.callbacks import ModelCheckpoint

...

checkpoint_callback = ModelCheckpoint(

monitor="val_loss", # which metric to track (val_loss is being logged in the validation_step method)

dirpath=ROOT_PATH / "models", # where to save checkpoints

filename="best-{epoch:02d}-{val_loss:.2f}", # filename format

save_top_k=1, # only save the best 1 model

mode="min" # save when val_loss is minimum

)This will create a file in your intro_mlops_2/models/ directory like best-epoch=25-val_loss=0.45.ckpt - the checkpoint from the epoch with the lowest validation loss. The save_top_k=1 means it only keeps the single best model, automatically deleting older checkpoints if a better one comes along.

|

By default, Lightning will create a |

Two important details about both callbacks:

- monitor="val_loss": Both callbacks rely on you logging val_loss in your validation_step method. If you forget to log it (or name it differently like validation_loss), these callbacks will not work because they cannot find the metric to monitor.

- mode="min": We use "min" because lower validation loss is better. If you were monitoring something like accuracy instead, you’d use mode="max" since higher accuracy is better.

We are also going to a simple logger to save the metrics to a CSV file in a custom directory. This way we can also track the metrics over time and compare them to the checkpoints. This is not strictly necessary but it is a good practice to do so.

Now let’s add these callbacks and logger to our trainer:

# main.py

from pytorch_lightning.loggers import CSVLogger

...

# Create a logger so metrics are also saved to a CSV file in a custom directory

csv_logger = CSVLogger(save_dir=str(BASE_DIR / "logs"), name="wine_quality")

# Add callbacks and logger to trainer

trainer = pl.Trainer(

max_epochs=model.hparams.epochs,

callbacks=[early_stopping, checkpoint_callback],

logger=csv_logger,

enable_progress_bar=False # this causes issues in the notebook, so we disable it, if you are running this in the command line i would recommend leaving it on

)

# Now we are training with callbacks and logging enabled (disabled progress bar since in notebook so added some prints to confirm training is happening)

def print_box(text, width=80):

print("=" * width)

print("|" + text.center(width - 2) + "|")

print("=" * width)

print_box("Training started...")

trainer.fit(model, datamodule=datamodule)

print_box("Training completed!")Benefits of This Setup

-

EarlyStopping: Prevents overfitting by stopping when validation loss stops improving.

-

ModelCheckpoint: Saves the best model automatically (you should see a new checkpoint file appear under

models/instead oflightning_logs/). -

Clean separation: Each component has a single responsibility.

-

Easy experimentation: Change configs without touching code.

Just to confirm lets see the contents of our logs/ directory:

# notebooks/your_notebook.ipynb

root_path = "~/project-04/intro_mlops_2/logs/" # adjust as needed

print_directory_tree(root_path, max_depth=3)

root_path = "~/project-04/intro_mlops_2/models/" # adjust as needed

print_directory_tree(root_path, max_depth=3)4.1 Run the pipeline (with no callbacks or logging) and check the output.

4.2 Show contents of the lightning_logs/ directory.

4.3 Run the pipeline with callbacks and logging enabled and check the output.

4.4 Show contents of the intro_mlops_2/logs/ directory.

Question 5 (2 points)

MLflow Logging & Saving the Model

MLflow is widely used in industry for experiment tracking, model registry, and deployment. Last question we integrated our Lightning module with our config files and callbacks and even adding some custom logging to a CSV file. Here we are going to implement a more robust logging solution using MLflow. We will log parameters, metrics, and the trained model so every run is reproducible and easy to compare.

Getting it set up is actually really simple. All you need to do is wrap your existing training in an MLflow run. By default MLflow saves runs under mlruns/ in the current directory (you can set MLFLOW_TRACKING_URI to use a different location).

# main.py

import mlflow # new import

import pytorch_lightning as pl

from pytorch_lightning.callbacks import EarlyStopping, ModelCheckpoint

# ... create model and datamodule from config as before ...

mlflow.set_experiment("WineQualityClassifier") # this is the name of the experiment that will be created in the MLflow UI

with mlflow.start_run():

# --- what we already had ...

# Log hyperparameters (from our config / Lightning module)

mlflow.log_params({

"epochs": model.hparams.epochs,

"learning_rate": model.hparams.learning_rate,

"model_class": model.model.__class__.__name__,

})

# Create callbacks and trainer, train as before

early_stopping = EarlyStopping(

monitor="val_loss",

patience=10,

mode="min"

)

checkpoint_callback = ModelCheckpoint(

monitor="val_loss",

dirpath="models/",

filename="best-{epoch:02d}-{val_loss:.2f}",

save_top_k=1,

mode="min"

)

trainer = pl.Trainer(

max_epochs=model.hparams.epochs,

callbacks=[early_stopping, checkpoint_callback]

)

trainer.fit(model, datamodule=datamodule)

# --- what we already had ...

# Log final validation metrics

val_results = trainer.validate(model, datamodule=datamodule)

if val_results:

for k, v in val_results[0].items():

mlflow.log_metric(k, v)

# Save the Lightning model with MLflow (full model; no need to reconstruct later)

# Get a sample batch to use as input_example for model signature

sample_batch = next(iter(datamodule.val_dataloader()))

sample_input = sample_batch[0][:1] # first sample from validation batch

mlflow.pytorch.log_model(model, name="model", input_example=sample_input.numpy())You can remove the old logic that used the CSVLogger and printed to the console or wrote results.log or saved only weights with torch.save, since MLflow now stores the full model and metrics for each run.

|

We are already doing this in the But just as a note, keep in mind that you still need to save the label encoder (e.g. to |

If your environment allows it, you can run mlflow ui in a terminal to open a local web UI and compare runs visually but in restricted environments (like on Anvil) you typically cannot open a server but you can still inspect runs programmatically (using Python code/API calls instead of a browser).

We will put all of that logic in a file called see_runs.py in your src/ folder. The file loads the runs, prints the table, plots val_loss and val_accuracy, and prints the best run. From your notebook you just call one function; you do not run any of the plotting or MLflow code in the notebook. Below is the full code that goes in the file, then we break it down into parts.

Part 1: Loading runs into a DataFrame

We first need to load the saved runs so we can start to use them which we can do by converting them to a Pandas DataFrame. We are going to create a function called load_mlflow_runs that uses the MLflow client to find the experiment by name, search its runs (newest first), and pull out the params and metrics we care about into a list of dicts. Turning that into a pandas DataFrame makes it easy to print, plot, or filter later.

# src/see_runs.py

import mlflow

from mlflow.tracking import MlflowClient

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from pathlib import Path

def load_mlflow_runs(experiment_name: str, max_runs: int = 20) -> pd.DataFrame:

"""Fetch recent runs for an experiment and return a DataFrame of params and metrics."""

# creates the client to the MLflow server

client = MlflowClient()

experiment = client.get_experiment_by_name(experiment_name)

if experiment is None:

return pd.DataFrame()

# this is looking for all the runs for our experiment and ordering them by start time in descending order (recent first)

runs = client.search_runs(

experiment_ids=[experiment.experiment_id],

order_by=["start_time DESC"],

max_results=max_runs,

)

# create a list of dictionaries with the run information to convert to a DataFrame

rows = []

for r in runs:

rows.append({

"run_id": r.info.run_id,

"start_time": r.info.start_time,

"epochs": r.data.params.get("epochs"),

"learning_rate": float(r.data.params.get("learning_rate", float("nan"))),

"val_loss": r.data.metrics.get("val_loss"),

"val_accuracy": r.data.metrics.get("val_accuracy"),

})

return pd.DataFrame(rows)Part 2: Displaying the table

Next we want to create a function called see_runs that will load the runs and print the table, plot val_loss and val_accuracy, and print the best run. We set the tracking URI so MLflow knows where to find your mlruns/ directory (e.g. at the project root), then calls load_mlflow_runs("WineQualityClassifier") to get that DataFrame.

We print the DataFrame so you can see all recent runs and their logged params (epochs, learning_rate) and metrics (val_loss, val_accuracy) in one table.

# src/see_runs.py

# ... loading the runs ...

def see_runs(experiment_name: str = "WineQualityClassifier", project_root=None, max_runs: int = 20):

if project_root is None:

project_root = Path(__file__).resolve().parents[2]

mlflow.set_tracking_uri(f"file://{project_root / 'mlruns'}") # otherwise mlflow will not know where to find the runs

# Load recent runs into a DataFrame

df_runs = load_mlflow_runs(experiment_name, max_runs=max_runs)

print(df_runs)

# more code to come...

return df_runs

if __name__ == "__main__":

see_runs()Part 3: Plotting val_loss and val_accuracy

The next block creates two bar charts side by side: one for final validation loss and one for final validation accuracy. Each run is a bar, so you can compare runs at a glance. plt.show() displays the figure (in a script or when you call see_runs() from a notebook, the plot window will appear).

# src/see_runs.py

# ... loading the runs ...

def see_runs(experiment_name: str = "WineQualityClassifier", project_root=None, max_runs: int = 20):

# ... loading the runs ...

# plotting the val loss and val accuracy for each run:

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(12, 4))

df_runs.plot(kind="bar", x="run_id", y="val_loss", ax=axes[0], title="Final val_loss", rot=45)

axes[0].set_xlabel("Run ID")

axes[0].set_ylabel("Validation Loss")

df_runs.plot(kind="bar", x="run_id", y="val_accuracy", ax=axes[1], title="Final val_accuracy", ylim=(0, 1), rot=45)

axes[1].set_xlabel("Run ID")

axes[1].set_ylabel("Validation Accuracy")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# more code to come ...

return df_runs

if __name__ == "__main__":

see_runs()Part 4: Finding the best run

We filter the DataFrame to the row with the minimum val_loss—that is the run that achieved the best validation loss. We print that run’s ID and its val_loss and val_accuracy so you know which run to use when loading a model for deployment (e.g. in your FastAPI app).

# src/see_runs.py

# ... loading the runs ...

def see_runs(experiment_name: str = "WineQualityClassifier", project_root=None, max_runs: int = 20):

# ... loading the runs ...

# ... plotting the runs ...

# you can also filter/sort runs to find the best one

best_run = df_runs.loc[df_runs["val_loss"].idxmin()]

print(f"Best run: {best_run['run_id']} with val_loss={best_run['val_loss']:.4f} and val_accuracy={best_run['val_accuracy']:.4f}")

return df_runs

if __name__ == "__main__":

see_runs()Calling the file from the notebook

From your notebook you only need to import and call see_runs(). It will print the table, show the plots, and print the best run.

# notebooks/your_notebook.ipynb

import sys

from pathlib import Path

PROJECT_ROOT = Path("../..").resolve() # adjust if needed

sys.path.insert(0, str(PROJECT_ROOT))

from intro_mlops_2.src.see_runs import see_runs

see_runs()This way we can now see which run had the best validation loss and accuracy to either use as a checkpoint or to deploy the model which we will do in the next question!

Note that since we are using all the same parameters for each run and we are setting the same seed for each run, the runs will be exactly the same. This is not always the case and you will often see runs with different parameters and different seeds which is why it is important to log the parameters and metrics for each run.

5.1 Training wrapped in an MLflow run with params and final validation metrics logged.

5.2 Model saved via mlflow.pytorch.log_model.

5.3 See the runs and the best run.

Question 6 (2 points)

Serving the Model with FastAPI

Last project we created a basic API using FastAPI to serve a prediction — but we skipped a critical step which is setting up input schema validation. This is essential for any API whether it is public or internal. It ensures you will not be sending malformed data into your model which can cause the model to fail outright, but the real danger are silent errors. Silent errors in this case would be when the API does not throw an error, the model returns a prediction, but the prediction is entirely incorrect. This is much worse because it can be hard to detect and someone could take action based on the wrong prediction. Rigorous validation helps defend against these risks.

Pydantic and Request/Response Schemas

Pydantic uses Python classes that inherit from BaseModel (an example can be found from their Pydantic examples page):

from pydantic import BaseModel, PositiveInt

class User(BaseModel):

id: int

name: str = 'John Doe'

tastes: dict[str, PositiveInt]Notice that they also have custom types such as PositiveInt. These help to restrict the domains of values even further if you know that for example the tastes attribute will never be a negative value.

We would typically pass a JSON object to an endpoint but last project we simply passed in an array to our endpoint which is not standard practice:

# app.py

@app.post("/predict")

def predict(data: list[float]): # not ideal

...So, let’s create a basic class object for our expected input to our API.

We could define this directly in app.py, but a cleaner and more scalable approach is to create a separate api_validation.py file inside the configs/ folder. This keeps your API logic clean and makes schema reuse easier later on (especially when you have multiple endpoints). We will also set up a response validation type:

# configs/api_validation.py

from pydantic import BaseModel

class WineQualityRequest(BaseModel):

alcohol: float

# add the rest of the feature fields to match your model's input (same order as training data)

class WineQualityResponse(BaseModel):

quality: str|

Depending on the number of features, making the Pydantic model may be tedious. For more advanced setups, you can dynamically create models, load input schemas from YAML or JSON config files, or create generic validators for tabular data! You can also use custom validators in your classes to implement checks beyond simple name and type checks. |

Loading the Model from MLflow and Wiring the Endpoint

Now we need to load the model we logged in Question 5 and use it in our API. We load from MLflow so we do not have to hardcode a run ID. Load the label encoder as before (e.g. from models/label_encoder.pkl).

# app.py - rewriting the code from last project

from mlflow.tracking import MlflowClient

import mlflow

def get_latest_model():

client = MlflowClient()

experiment = client.get_experiment_by_name("WineQualityClassifier")

latest_run = client.search_runs(experiment_ids=[experiment.experiment_id], order_by=["start_time DESC"], max_results=1)[0]

model_uri = f"runs:/{latest_run.info.run_id}/model"

return mlflow.pytorch.load_model(model_uri)

app = FastAPI()

model = get_latest_model()

model.eval()

# Load label encoder (e.g. from models/label_encoder.pkl)Now, import WineQualityRequest and WineQualityResponse into app.py and set up your validation:

# app.py

# ... other imports ...

from intro_mlops_2.configs.api_validation import WineQualityRequest, WineQualityResponse

# ... loading model and label encoder ...

@app.post("/predict", response_model=WineQualityResponse)

async def predict(input_data: WineQualityRequest):

features = torch.FloatTensor([

input_data.alcohol,

# ... other feature fields in the same order as your training data

]).unsqueeze(0)

with torch.no_grad():

logits = model(features)

pred_idx = logits.argmax(dim=1).item()

predicted_label = label_encoder.inverse_transform([pred_idx])[0]

return {"quality": ["Bad", "Mid", "Good"][pred_idx]By specifying that the input type to your FastAPI endpoint is a Pydantic class, FastAPI will automatically validate the incoming data when you attempt to access it. If it is not of the correct format it will return an error specifying what was malformed. If it is correct you should receive back the response in the WineQualityResponse format.

Please run the API in a terminal window similar to how you did last project from the project root (the directory that contains intro_mlops_2/):

python -m uvicorn intro_mlops_2.app:app --reload --host 0.0.0.0 --port 8000In our notebook, we are going to send two requests to our newly fortified endpoint to check that it is working with different data inputs:

# Invalid: sending an array instead of a JSON object with the expected keys

data = [5.1, 3.5, 1.4, 0.2]The above should return a 422 error message stating that the request is not valid and showing the details Pydantic found wrong with the request.

Now, let’s send a valid request:

# Valid: JSON object with all feature fields (fill in your actual feature names and values)

data_good = {

'fixed_acidity': 6.2,

'volatile_acidity': 0.28,

'citric_acid': 0.27,

'residual_sugar': 10.3,

'chlorides': 0.03,

'free_sulfur_dioxide': 26.0,

'total_sulfur_dioxide': 108.0,

'density': 0.99388,

'pH': 3.2,

'sulphates': 0.36,

'alcohol': 10.7,

'quality': 6

}You should get back {'quality': 'Mid'} as the response!

Now please make your own combination and send it in! If you want you can sample a row from the dataset and convert it to a dict like so:

df.sample(n=1).drop(['type'], axis=1).to_dict(orient="records")[0]This way you can compare by hand what your model predicted and what the dataset shows!

# i.e.:

data = {

"alcohol": 10.2,

# ... rest of your feature keys and values

}6.1 Request/response validation with Pydantic (WineQualityRequest and WineQualityResponse).

6.2 Model loaded from MLflow (e.g. via get_latest_model) and used in FastAPI.

6.3 Output from an invalid formatted request (should error).

6.4 Output from a valid formatted request (should succeed).

Submitting your Work

Once you have completed the questions, save your Jupyter notebook. You can then download the notebook and submit it to Gradescope.

-

firstname_lastname_project5.ipynb

|

It is necessary to document your work, with comments about each solution. All of your work needs to be your own work, with citations to any source that you used. Please make sure that your work is your own work, and that any outside sources (people, internet pages, generative AI, etc.) are cited properly in the project template. You must double check your Please take the time to double check your work. See here for instructions on how to double check this. You will not receive full credit if your |