TDM 30200: Project 3 - Containers & RESTful APIs

Project Objectives

We are going to cover the basics of RESTful APIs and Apptainer, a Docker like product. This will build a simple baseline project that is easily expandable into almost any project you would work on.

Dataset

-

None for this project

|

If AI is used in any cases, such as for debugging, research, etc., we now require that you submit a link to the entire chat history. For example, if you used ChatGPT, there is an “Share” option in the conversation sidebar. Click on “Create Link” and please add the shareable link as a part of your citation. The project template in the Examples Book now has a “Link to AI Chat History” section; please have this included in all your projects. If you did not use any AI tools, you may write “None”. We allow using AI for learning purposes; however, all submitted materials (code, comments, and explanations) must all be your own work and in your own words. No content or ideas should be directly applied or copy pasted to your projects. Please refer to the-examples-book.com/projects/spring2026/syllabus#guidance-on-generative-ai. Failing to follow these guidelines is considered as academic dishonesty. |

Useful Things

-

A lot of this project is done within the terminal and we will just have some ways to verify your work in the Notebook.

-

Similar to other projects that are not purely in a notebook, you will need to create a clean working directory for this project.

-

You will need to base the file paths provided to you in the handout based on your filesystem.

|

Do NOT try to run all these things in the Notebook because they likely will not work. The handout should explicitly say where you need write something and when you need to run something in your notebook. |

Questions

Question 1 (2 points)

Containers - What are they?

If you have ever worked on production code, you have probably run that code in some type of container, most likely Docker. Docker is commonly used in industry.

But due to the current status of Anvil, we cannot run Docker very easily, so we are using Apptainer instead. It is similar in principle to Docker but has some key differences that make it more fitted for running on HPC (High Performance Computing) environments because of those implementation differences.

Right, but what actually is a container and what do they do?

Containers at their core provide a common working environment for your code - no matter where it is. The age old excuse of "well it works on my computer" is effectively nullified when you consider using containers. What’s even more convenient is that as long as the device can run the container software (which most devices can) then your software can run there. No problem. Much fewer compatibility issues!

Don’t tell my boss but this is a nice video talking about this: click here

That sounds nice but if you have heard of virtual machines you may ask why would we need containers? Well, there are a few good reasons.

It really depends on your application, but most of the time running entire virtual machine, either virtualized or emulated, is much much heavier on your system than just creating a container, especially if you are deploying multiple containers or hosting your product on less beefy devices. Virtual machines are also generally less compatible than container software.

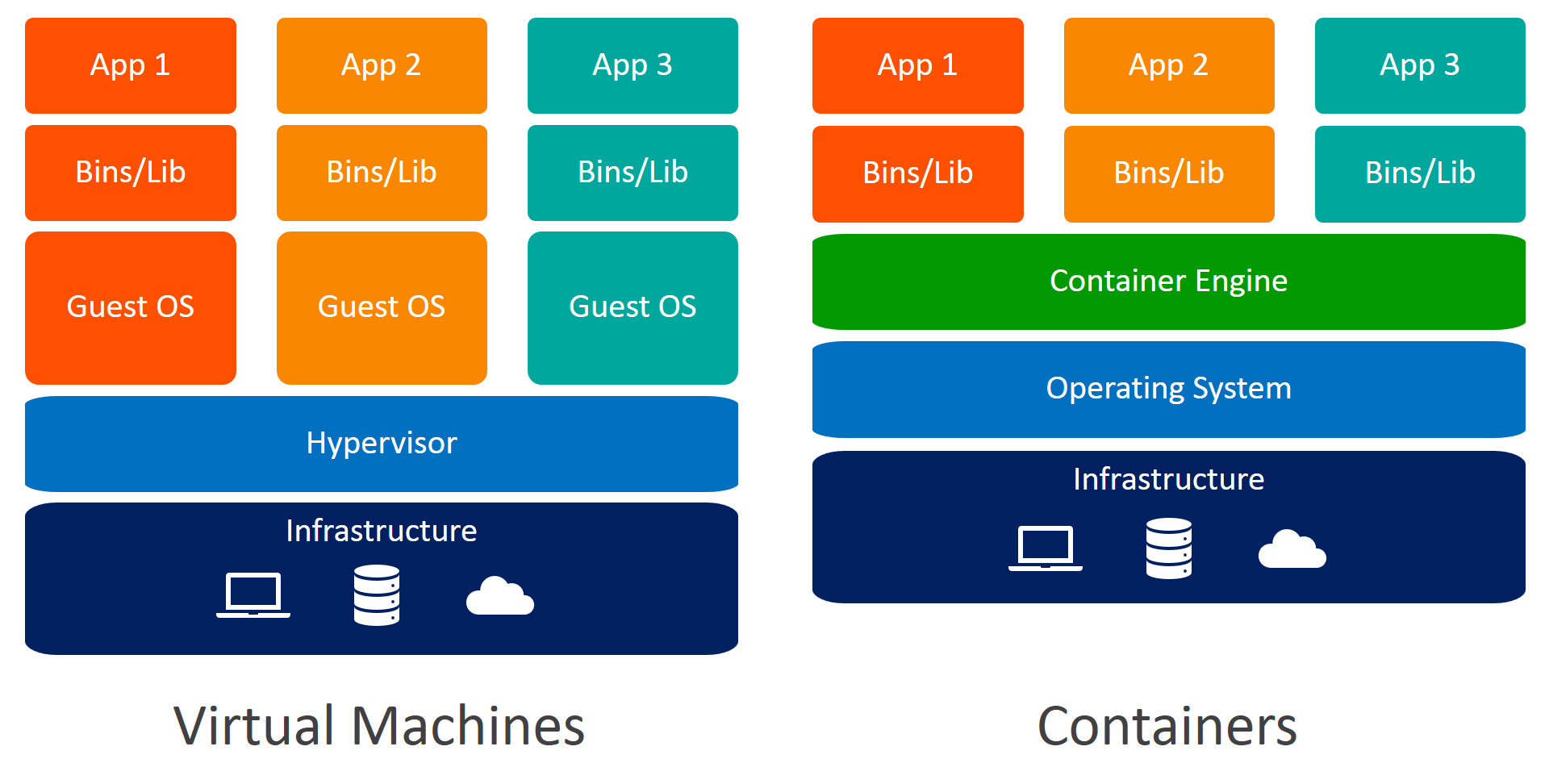

The image below provides a visualization on the differences between containers and virtual machines. Containers will create a basic filesystem for your program to use while running but it will not bother running an entirely new OS layer for every container deployed.

Since the containers can be run on one shared operating system, use the same lightweight container engine to manage containers, it saves a lot of resources and also simplifies things like communication between containers since the engine typically can help handle that routing.

So how do you make a container?

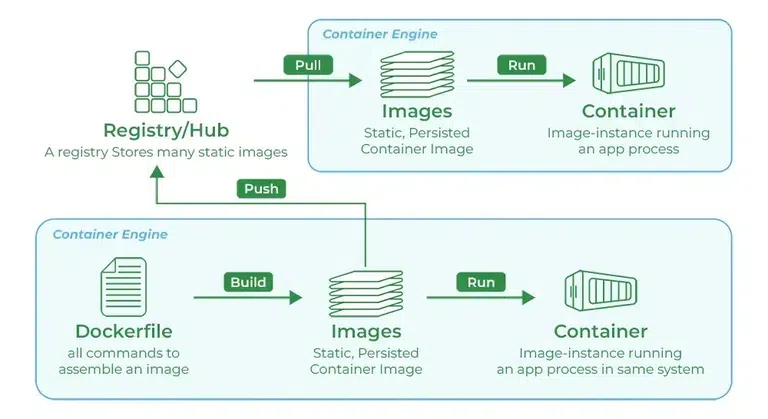

You need something called an image. You typically start by using a base preset of whatever kind of software you need. For example, if you want to run a Python service, then you can create a Python based image, if you want to create a JavaScript app then you can create a Node based image. If you want to create a Postgres container, you can create a Postgres based image, etc. Different container services provide access to these base images slightly different but the idea is the same - there is some central registry that stores different versions of prebuilt, ready to use images for many types of software you can pull down.

Once you have the starting image, you can also create your own custom images and push them to these registries that people can pull down from, too. The process is shown visually below:

|

Even though the graphic says "Dockerfile", the concept is the same for Apptainer. Apptainer even lets you bootstrap images from the Docker registry which is very convenient! |

Some of this may seem a little abstract, but once we get into creating our own images in the next question, some of the potential confusion should be cleared up.

Feel free to read more about containers and registries from the two links provided and please answer the questions in the deliverable:

www.geeksforgeeks.org/devops/what-is-docker-registry

www.bmc.com/blogs/containers-vs-virtual-machines

1.1 Write 2-3 sentences explaining what a container is.

1.2 Write 2-3 sentences explaining what images and registries are.

Question 2 (2 points)

Creating an Apptainer Service

Now that we have a general idea of what a container is, let us define one.

But first let’s make a simple script that we want to run inside our container. Outside of the Notebook (in terminal or file explorer), create a script called hello.py that logs "Hello world!" every few seconds using Python’s standard library logging module:

# project3/hello.py

import logging

from datetime import datetime

from time import sleep

# this will log everything into a file called hello.log

logging.basicConfig(

level=logging.INFO,

filename="hello.log",

format="%(asctime)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s",

)

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

def main():

while True:

logger.info("%s - Hello world!", datetime.now().time())

sleep(3)

logger.info("End of function!")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()|

As always please make sure to create a clean working directory for this project. i.e. "project3/hello.py" |

For simplicity we are going to manually create a requirements.txt to avoid issues with the seminar kernel environment when installing dependencies into the container. Create this in the same spot as your hello.py (we don’t actually need pandas here, we just need something as placeholder):

# project3/requirements.txt

pandas==2.3.2Now we can create a file called Apptainer.def - .def is the specific file type used to define your image for Apptainer. This is a brief overview of some of the main sections of a Apptainer definition file:

# project3/Apptainer.def

Bootstrap: # registry location you are bootstrapping from

From: # the image you want to pull from the registry

%files

# this is where you copy over the relevant files from your local workspace to your container workspace

%post

# this is where you run the necessary bash commands to create the environment you want for your program to run in

# i.e. customizing base file structure, updating dependencies to ensure a stable environment, installing python requirements into the environment

%environment

# this is where you can define environment variables you may need

%runscript

# this is where you run the script that for your program|

Note that Apptainer has a set order of executing the sections during build time: bootstrap → files → post → environment → runscript So the order in which you write your sections does not matter - it simply is a matter of personal preference. Some people may write |

Let’s go through this section by section.

Defining Base Image

We mentioned in the last problem that we can just use the Docker registry even though we are using Apptainer. We can set the location we are pulling from to be the default Docker registry by specifying the Bootstrap parameter. We also want to grab a Python image from that registry so we can run our program:

# project3/Apptainer.def

Bootstrap: docker

From: python:3.11-slimWe specified the location to be docker and then our base image to be python:3.11-slim.

Slim is a lighter-weight variant of the official Python image (smaller than the full image but still Debian-based). You often don’t need the full Python installation for your app, so using slim saves image size and build time. We use slim rather than Alpine here because many Python packages with C extensions (e.g. NumPy, cryptography) build more reliably on Debian/glibc; Alpine uses musl libc and can require more work to get some wheels building.

File Mapping - %files

Like just mentioned, this runs prior to %post. This is where we map/move the files from our local workspace to inside the container. For a small example like this we do not need much, something as simple as:

. /appwill do. This takes all files in the current directory and copies them into a folder called /app in the container’s filesystem (it will automatically create the directory /app for us)

Setting Up Environment - %post

Now we have our basic Linux environment with Python installed and our necessary app files moved over, its generally good practice to update your Linux and ensure dependencies for your Python installation are up to date.

At the most basic level we can just run:

# update and install build dependencies

apt-get update && apt-get install -y gcc libc-dev && rm -rf /var/lib/apt/lists/*Some Python libraries like numpy, pandas, psycopg2, cryptography etc. all have some native code written in C, so we need to make sure C compilers (gcc & libc-dev) are installed in our environment so the packages can properly compile when we install them into our environment.

We then remove the files in /var/lib/apt/lists/* because these are files created by the commands apt-get update && apt-get install which are only needed during the installation of the packages. Once the necessary dependencies are installed, we can remove them to reduce bloat and have a slimmer final image.

Now that our Linux is updated and we have the base dependencies we need installed. We then install our requirements into our environment which we can do like so:

# install python dependencies

pip install --no-cache-dir -r /app/requirements.txtNote that since we are in a separated workspace, installing globally is okay, in fact it is generally done this way. There is not much need to worry about creating a virtual environment when you are working in a container since it is an entirely clean and isolated environment.

Defining Environment Variables - %environment

If you recall from last fall in TDM 301 / TDM 401 Project 2 we had to do some workaround with the PATH environment variables, here is another application of where we will specify environment variables like PATH to make sure we use the correct Python and such.

export PATH=/home/$USER/.local/bin:$PATH

export HOME=/home/$USER

export APP_DIR=/appWe prepend our PATH with /home/$USER/.local/bin so when running commands, our shell will know to look in ./local/bin for the Python environment that we have installed our requirements into.

We specify HOME in case some other tools rely on the environment variable HOME - if we didn’t have it set then the tools may break since they are trying to point to an invalid place.

This part is optional, but we choose to add APP_DIR here which just gives us the option to use that as a shortcut to specify certain paths. For some more complex projects, it may be convenient to create these environment variables. One reason is that in case you refactor general structure, then you do not necessarily need to go through a bunch of different paths and fix them, you can just fix the environment variables.

Running The Script - %runscript

The final section is generally very simple. For our case all we need to tell it to execute the main script. Add this into the %runscript section:

exec python /app/hello.pyWe could also use our environment variable APP_DIR and do this:

exec python $APP_DIR/hello.pyBuilding the Container

Now we can build the container and run our program. Run this in the command line:

apptainer build myapp.sif Apptainer.defThis may take a minute and sometimes it says it will take an hour or more, but the time fluctuates a lot. It typically only took ~30 seconds to build.

Now we have a .sif file which is pure compiled program that now can be moved anywhere and run anywhere!

Let’s run it with (in the command line):

apptainer run myapp.sifNotice that there is no output in the terminal because we are logging to a file. You can view the output in the hello.log file in the project3 directory which gets updated each loop of the script.

Let it run for ~10 seconds and then please use ctrl+C to stop the script.

We can also add a handler to log to the terminal so we can see the output in the terminal:

# project3/hello.py

...

logging.basicConfig(

... # same as above

)

logging.getLogger().addHandler(logging.StreamHandler()) # adding this will log to the terminal

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)Please add this to your script, rebuild the container, and run it again. You should now see the output in the terminal. Once again, let it run for ~10 seconds and then please use ctrl+C to stop the script.

2.1 In your Notebook, please run ls [your project directory].

2.2 In your Notebook, please run cat [your project directory]/hello.log.

Question 3 (2 points)

What is a RESTful API? (Is it sleepy?)

First what is an API? It is an Application Programming Interface. It is a contract that defines how two programs can talk to each other.

For example, if you check the weather app on your phone, its not going out and scraping the data itself. It is pinging a clean predefined API endpoint requesting information. The API then just passes the information back to the requester. It is essentially a messenger between systems where one app makes a request, the API decides what is allowed and what to do and then responds appropriately.

APIs allows communication between different systems and gives you stricter control of what each application can know about the other. When working with live users, you definitely do not want them to be able to access the database itself because it opens the doors for many more security vulnerabilities, hence you can use an API to manage how the data is accessed and modified.

Now what is REST? It stands for Representational State Transfer which is a set of standard design principles used for building APIs. Adhering to the standards allows for increased interoperability, increased consistency and increased ease of use.

A RESTful API will typically expose endpoints that map to the CRUD operations:

- Create → add new data

- Retrieve → retrieve existing data

- Update → modify data

- Delete → remove data

These CRUD operations typically map to HTTP methods:

| HTTP Verb | Meaning | Example | CRUD Mapping |

|---|---|---|---|

GET |

Fetch data (read only) |

GET /items/1 → returns item 1 |

Retrieve |

POST |

Create a new resource |

POST /items with body { "value": "abc" } |

Create |

PUT |

Replace an existing resource entirely |

PUT /items/1 with new body |

Update |

PATCH |

Modify part of an existing resource |

PATCH /items/1 with { "value": "xyz" } |

Partial Update |

DELETE |

Remove a resource |

DELETE /items/1 |

Delete |

Hands on

Please create a new directory and file /api/main.py. This directory will house our API related files.

We will import FastAPI which is a very popular library that lets you create API routes in Python. We will get more into it in the next problem.

# api/main.py

import logging

from datetime import datetime

from fastapi import FastAPI, HTTPException

logging.basicConfig(

level=logging.INFO,

filename="api.log",

format="%(asctime)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s",

)

# Also log to stdout so you see output in the terminal

logging.getLogger().addHandler(logging.StreamHandler())

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)We can then create a FastAPI object to create our demo API on. The title is completely optional but should be relevant to whatever you are doing.

Next, we are now going to add the most basic route we can just to test and establish the connection.

# api/main.py

app = FastAPI(title="Student Demo API")

@app.get("/")

def read_welcome():

logger.info("Welcome endpoint hit at %s", datetime.now().time())

return {"message": f"{[datetime.now().time()]} Welcome to a simple demo!"}This creates a GET route which we just talked about above. This is the simplest version you can make which just returns some information that doesn’t necessarily require parameterization - things like a static text retrieval or a single point of information you want to define a specific route for. You can still pass parameters to this route if you want to do a complex fetching operation!

|

Recall what REST means and its function. Note that GET, POST, DELETE etc. exist as part of this convention. For example, you can perform delete operations from within a GET route; however, that breaks the intention of creating a standard set of operations each route type handles. |

Now that we have a simple route, we will also need to update our image definition to serve up this API instead of our test script we had last time. Create a copy of Apptainer.def in the api directory with the following modification:

# api/Apptainer.def

...

# old:

%runscript

exec python $APP_DIR/main.py

# new:

%runscript

exec uvicorn main:app --host 127.0.0.1 --port 8000 --reload --app-dir /appPlease also create a requirements.txt file in the api directory with the following content:

# api/requirements.txt

fastapi==0.104.1

uvicorn==0.24.0Now, let’s build and run the modified image. In a terminal session within the /api directory:

apptainer build api.sif Apptainer.def

apptainer run api.sifWe should now be hosting our API and be able to hit our endpoint at "http://127.0.0.1:8000".

|

You might wonder why we use "127.0.0.1" instead of "0.0.0.0" since most of the time when testing locally, they are interchangeable, but there is a slight difference in this context: Apptainer automatically maps the container’s port 8000 to your host machine’s port 8000, making it accessible at |

Now, in your notebook we are going to make an HTTP request to the API we just served. The nice thing about APIs served on HTTP and following standard REST principles is that you can make requests to that API from any language as long as it can hit an HTTP endpoint. You can host your server in Python using FastAPI but have a frontend written in TypeScript - they can all communicate through HTTP requests.

Now we will make a request to the endpoint and we will be able to get the information from it.

import requests

from time import sleep

for _ in range(5):

response = requests.get("http://127.0.0.1:8000/")

print(response.json())

sleep(1)Answer the questions below and show the output from the provided code in your Notebook.

3.1 For the following scenarios explain what HTTP method and endpoint structure you would use:

- A librarian wants to add a new book to the catalog,

- A student wants to check if a book is available,

- A librarian needs to remove a book that was lost,

3.2 Output from making the API call.

Question 4 (2 points)

More FastAPI

We briefly touched on FastAPI but let’s get more into it and expand on our API now that we have a baseline.

Since setting up a whole database for our API to ping is a little out of scope and not the primary objective here, we will just define a local temporary dummy dictionary to mimic writing to a database.

# api/main.py

app = ...

# our in-memory "database"

items = {}

@app.get("/")

...|

This in-memory dictionary acts as our temporary "database" for this demo. In a real application, this would be replaced with an actual database like PostgreSQL, MySQL, or MongoDB. The dictionary will store our items with their IDs as keys and values as the stored data. Since it’s in-memory, all data will be lost when the container stops, but it’s good enough for demonstrating how the API endpoints work. |

Routes Explained

Each route below represents one of the main CRUD operations. They all take one parameter item_id: int and use that to perform that operation in our (local) database. Each one of the routes below also has some basic error handling which is standard practice to ensure API safety as well as logging to the terminal and file.

GET → Retrieve This fetches an item by its ID. If the ID does not exist, it returns a 404 error.

# api/main.py

...

@app.get("/items/{item_id}")

def read_item(item_id: int):

if item_id not in items:

logger.warning("Item not found: %s", item_id)

raise HTTPException(status_code=404, detail="Item not found")

logger.info("Read item %s", item_id)

return {"id": item_id, "value": items[item_id]} # core logicPOST → Create This creates a new item. If the item already exists, it returns a 400 error.

# api/main.py

...

@app.post("/items/{item_id}")

def create_item(item_id: int, value: str):

if item_id in items:

logger.warning("Item already exists: %s", item_id)

raise HTTPException(status_code=400, detail="Item already exists")

items[item_id] = value # core logic

logger.info("Created item %s: %s", item_id, value)

return {"message": "Item created", "id": item_id, "value": value}PUT → Update This updates an existing item. If the item does not exist, it returns a 404 error.

# api/main.py

@app.put("/items/{item_id}")

def update_item(item_id: int, value: str):

if item_id not in items:

logger.warning("Item not found on update: %s", item_id)

raise HTTPException(status_code=404, detail="Item not found")

items[item_id] = value # core logic

logger.info("Updated item %s: %s", item_id, value)

return {"message": "Item updated", "id": item_id, "value": value}DELETE → Remove This deletes an existing item. If the item does not exist, it returns a 404 error.

# api/main.py

@app.delete("/items/{item_id}")

def delete_item(item_id: int):

if item_id not in items:

logger.warning("Item not found on delete: %s", item_id)

raise HTTPException(status_code=404, detail="Item not found")

del items[item_id] # core logic

logger.info("Deleted item %s", item_id)

return {"message": "Item deleted", "id": item_id}Now that we have all our CRUD routes defined, let’s rebuild and run our container with the updated API:

apptainer build api.sif Apptainer.def

apptainer run api.sifJust like last problem, the API will start and be available at 127.0.0.1:8000. You can also test if the API is responding by making a simple request. Please run this in your notebook:

!curl http://127.0.0.1:8000/This will show you that port 8000 is being used by your containerized API and that it’s responding to requests.

Now let’s test our API by making a series of requests to demonstrate all the CRUD operations. We’ll go through each operation step by step in your notebook:

|

Since refreshing the API will reset the database, you will need to create new items after each reload so keep that in mind when trying to test the endpoints and get the correct output. |

import requests

# Base URL for our API

base_url = "http://127.0.0.1:8000"1. CREATE - Adding Items to Our Database

First, let’s add some items to our database using POST requests. This demonstrates the Create operation in CRUD:

# Create three items with different IDs and values

response1 = requests.post(f"{base_url}/items/1", params={"value": "Hello World"})

print("Created item 1:", response1.json())

response2 = requests.post(f"{base_url}/items/2", params={"value": "FastAPI Demo"})

print("Created item 2:", response2.json())

response3 = requests.post(f"{base_url}/items/3", params={"value": "Container API"})

print("Created item 3:", response3.json())2. READ - Retrieving Items from Our Database

Now let’s retrieve the items we just created using GET requests. This demonstrates the Read operation:

# Read each item we created

for item_id in [1, 2, 3]:

response = requests.get(f"{base_url}/items/{item_id}")

print("Retrieved item:", response.json())Notice we use template strings to dynamically specify the ID of the item we are trying to read from the database.

3. UPDATE - Modifying an Existing Item

Let’s update one of our items using a PUT request. This demonstrates the Update operation:

# Update item 2 with a new value

response = requests.put(f"{base_url}/items/2", params={"value": "Updated FastAPI Demo"})

print("Updated item 2:", response.json())4. READ - Verifying Our Update Worked

Let’s verify that our update actually worked by reading the item again:

# Read item 2 to confirm the update

response = requests.get(f"{base_url}/items/2")

print("Item 2 after update:", response.json())5. DELETE - Removing an Item

Now let’s delete one of our items using a DELETE request. This demonstrates the Delete operation:

# Delete item 3

response = requests.delete(f"{base_url}/items/3")

print("Deleted item 3:", response.json())6. Error Handling - Trying to Read a Deleted Item

Let’s see what happens when we try to read an item that no longer exists:

# Try to read the deleted item (should get 404 error)

response = requests.get(f"{base_url}/items/3")

print("Status Code:", response.status_code)

print("Response:", response.json())We should get a 404 status code with a "Item not found" message. This demonstrates how our API handles errors gracefully by returning appropriate HTTP status codes and error messages.

A good API will have good error handling specifying the issues that can occur and providing a fallback for any unexpected situations.

Notice the same thing will happen if we try to delete an item that doesn’t exist.

Please attempt this in your notebook so we can see the output.

7. Your Turn - Try Creating Your Own Item

Now it’s your turn! Try creating a new item with ID 4 and any value you want. Fill in the code below:

# TODO: Create item 4 with your own value

response = requests.____(f"", params=)We just did a series of requests to the API and we can see the output from each request. Just for fun, let’s add a route that will dump all the items in our database:

# api/main.py

@app.get("/dump-items")

def dump_items():

if not items:

raise HTTPException(status_code=404, detail="No items found")

return {"items": items}|

FastAPI automatically refreshes itself every time you make a change in API definition file; however, since we are running it in a container you may need to rebuild the container to be able to hit the new endpoint! |

Please make a request to the /dump-items endpoint and show the output in your notebook.

This will show you the final state of your in-memory database after all the operations we performed.

You typically do not want to dump the entire database to the API since that can be a security vulnerability. However, for the sake of this project, we are going to do it.

4.1 Output showing port 8000 is running and the API is serving.

4.2 Output from the requests sent to the API (Successfully write, read, update, delete).

4.3 Output from the error handling (Failed read, Failed delete).

4.4 Output from your own POST to the endpoint.

4.5 Output from the /dump-items endpoint.

Question 5 (2 points)

Creating a Second Container

Typically you would not be using Apptainer in a multi container setup since it’s meant to be a single application running not a multi service tool but we are going to ignore that for the sake of this project. Since the port for the API is already exposed, we are going to do a very similar thing that we did last problem but this time have two containers running - one being the API we made last problem and one acting as some user/application pinging the API for some information.

Setting Up Multi-Container Communication

In a real-world scenario, you might have:

- A backend API (like we just built),

- A frontend application that consumes the API,

- An ETL pipeline that writes data to a database,

- A monitoring service that checks API health.

For this demo, we’ll create a "client" container that simulates a frontend application making requests to our API.

Creating the Client Container

First create a new directory called client at the same level as the api directory. Then create a new file called main.py:

# client/main.py

import logging

import random

import requests

import time

from datetime import datetime

logging.basicConfig(

level=logging.INFO,

filename="client.log",

format="%(asctime)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s",

)

logging.getLogger().addHandler(logging.StreamHandler()) # adding it from the start this time

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)Our main logic for this simulated frontend is just going to randomly create, read, update, and delete items from the API which we can do with something like this:

# client/main.py

# set seed for reproducible results

random.seed(42)

def make_random_requests():

base_url = "http://127.0.0.1:8000"

# list of possible operations - simple way to add bias to creating & reading

operations = ["create", "read", "read", "update", "delete", "create"]

# some random values for our items

values = ["Random Data", "Test Item", "Demo Value", "Sample Text", "API Test"]

logger.info("=" * 80)

logger.info("Starting client requests at %s", datetime.now())

logger.info("=" * 80)

for i in range(10): # make 10 random requests

operation = random.choice(operations)

item_id = random.randint(1, 15) # trying to randomly cause collisions

value = random.choice(values)

try:

if operation == "create":

response = requests.post(f"{base_url}/items/{item_id}", params={"value": value})

logger.info("CREATE item %s: %s - %s", item_id, response.status_code, response.json())

elif operation == "read":

response = requests.get(f"{base_url}/items/{item_id}")

logger.info("READ item %s: %s - %s", item_id, response.status_code, response.json())

elif operation == "update":

response = requests.put(f"{base_url}/items/{item_id}", params={"value": f"Updated {value}"})

logger.info("UPDATE item %s: %s - %s", item_id, response.status_code, response.json())

elif operation == "delete":

response = requests.delete(f"{base_url}/items/{item_id}")

logger.info("DELETE item %s: %s - %s", item_id, response.status_code, response.json())

except Exception as e:

logger.error("Error with %s on item %s: %s", operation, item_id, e)

# Small delay between requests to be respectful of the server

time.sleep(1)

logger.info("=" * 80)

logger.info("Finished client requests at %s", datetime.now())

logger.info("=" * 80)

if __name__ == "__main__":

make_random_requests()Now let’s create a requirements file for our client:

# client/requirements.txt

requests==2.31.0Creating the Client Container Definition

Create a new file called client/Apptainer.def:

# client/Apptainer.def

Bootstrap: docker

From: python:3.11-slim

%files

main.py /app/main.py

requirements.txt /app/requirements.txt

%post

# Update and install dependencies

apt-get update && apt-get install -y gcc libc-dev && rm -rf /var/lib/apt/lists/*

# Install Python dependencies

pip install --no-cache-dir -r /app/requirements.txt

%environment

export PATH=/home/$USER/.local/bin:$PATH

export HOME=/home/$USER

export APP_DIR=/app

%runscript

exec python /app/main.pyRunning Both Containers

Now we need to run both containers. Since Apptainer doesn’t have built-in networking like Docker, we’ll need to run them in separate terminal sessions.

Terminal 1 - Start the API container:

apptainer run api.sifTerminal 2 - Start the client container:

apptainer build client.sif Apptainer.def

apptainer run client.sifChecking the Results

Let’s check what happened by looking at the logs in two different cells in your notebook:

cat api/api.logcat client/client.logYou should see the client making various requests to the API, and the API responding with appropriate status codes and messages.

Understanding Multi-Container Communication

This setup we have here demonstrates how different containers can communicate through HTTP requests, even though Apptainer isn’t designed for this use case. In a real Docker environment, you would use something like:

-

Docker Compose to orchestrate multiple containers

-

Docker networks for secure container-to-container communication

-

Service discovery to automatically find other containers

-

Load balancers to distribute requests across multiple API instances

|

If you want to know a little more about the differences between Docker and Apptainer then there is some more information in Question 6 of TDM 401. Obviously you do not need to do it but if you want to learn a little more feel free. |

5.1 Output from cat api/api.log showing API requests being received.

5.2 Output from cat client/client.log showing the randomized requests made.

5.3 Brief explanation (1-2 sentences) of how the containers communicated.

Submitting your Work

Once you have completed the questions, save your Jupyter notebook. You can then download the notebook and submit it to Gradescope.

-

firstname_lastname_project3.ipynb

|

It is necessary to document your work, with comments about each solution. All of your work needs to be your own work, with citations to any source that you used. Please make sure that your work is your own work, and that any outside sources (people, internet pages, generative AI, etc.) are cited properly in the project template. You must double check your Please take the time to double check your work. See here for instructions on how to double check this. You will not receive full credit if your |