STAT 39000: Project 8 — Fall 2021

Motivation: Python is an incredible language that enables users to write code quickly and efficiently. When using Python to write code, you are typically making a tradeoff between developer speed (the time in which it takes to write a functioning program or scripts) and program speed (how fast your code runs). This is often the best choice depending on your staff and how much your software developers or data scientists earn. However, Python code does not have the advantage of being able to be compiled to machine code for a certain architecture (x86_64, ARM, Darwin, etc.), and easily shared. In Python you need to learn how to use virtual environments (and git) to share your code.

Context: This is the last project in a series of 3 projects that explores how to setup and use virtual environments, as well as some git basics. In addition, we will use this project as a transition to learning about APIs.

Scope: Python, virtual environments, git, APIs

Dataset(s)

The following questions will use the following dataset(s):

-

/depot/datamine/data/whin/whin.db

Questions

|

We are so lucky to have great partners in the Wabash Heartland Innovation Network (WHIN)! They generously provide us with access to their API (here) for educational purposes. You’ve most likely either used their API in a previous project, or you’ve worked with a sample of their data to solve some sort of data-driven problem. You can learn more about WHIN at here. In this project, we are providing you with our own version of the WHIN API, so you can take a look under the hood, modify things, and have a hands-on experience messing around with an API written in Python! Behind the scenes, our API is connecting to a sqlite database that contains a small sample of the rich data that WHIN provides. |

Question 1

In a previous project, we used the requests library to build a CLI application that made calls to the WHIN API.

Our focus in this project will be to study the WHIN API (and other APIs), with the goal of learning about the components of an API in a hands-on manner.

Before we really dig in, it is well worth our time to do some reading. There is a lot of information online about APIs. There are a lot of opinions on proper API design.

|

At no point in time will we claim that the way we are going to design our API is the best way to do it. However, we will try and learn from some of the most successful commercial APIs, mainly, the Stripe API. |

First thing is first, let’s clone our homage to the WHIN API to prevent confusion, we will refer to this as our API. Run the following in a bash cell.

%%bash

cd $HOME

git clone [email protected]:TheDataMine/f2021-stat39000-project8.gitThen, install the Python dependencies for this project by running the following code in a new bash cell.

%%bash

module unload python/f2021-s2022-py3.9.6

cd $HOME/f2021-stat39000-project8

poetry installFinally, let’s see if we can run this API on Brown! To do this, we will not be running the API via a bash cell in Jupyter Lab. Instead, we will pop open a terminal, and have it running in another tab.

Create a file called .env (that’s it, no extension — just a file called .env with the following text, in a single line) inside your f2021-stat39000-project8 directory, with the following content.

DATABASE_PATH=/depot/datamine/data/whin/whin.db

|

A file starting with a period is a hidden file. In UNIX-like systems, you need to add Give it a try: |

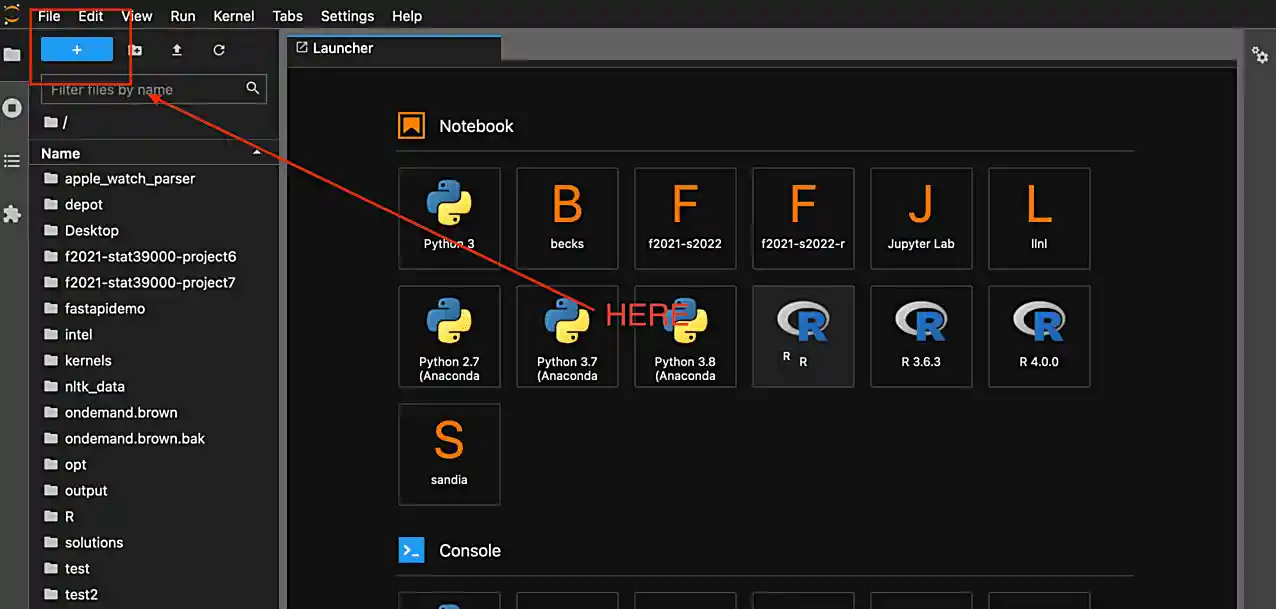

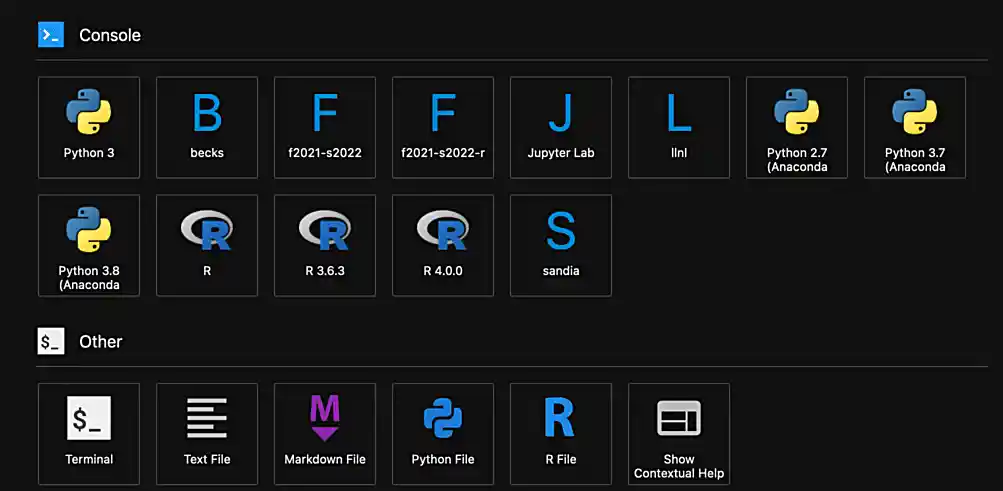

Then, open a new terminal tab. Click on the blue "+" button in the top left corner of the Jupyter Lab interface.

Then, on your kernel selection screen, scroll down until you see the "Terminal" box. Select it to launch a fresh terminal on Brown.

The command to run the API is as follows.

module use /scratch/brown/kamstut/tdm/opt/modulefiles

module load poetry/1.1.10

cd $HOME/f2021-stat39000-project8

poetry run uvicorn app.main:app --reloadNow, with that being said, it is not quite so simple. We are running this API on Brown, a community cluster with lots of other users, running lots of other applications. By default, fastapi will run on local port 8000. What this means is that if you were on your personal computer, you could pop open a browser and navigate to localhost:8000/ to see the API. The problem here is you each need to be running your API on your own port — and it is very likely port 8000 is already in use.

So what are we going to do? Well, one option is to just choose a number, and run your API with this command.

module use /scratch/brown/kamstut/tdm/opt/modulefiles

module load poetry/1.1.10

cd $HOME/f2021-stat39000-project8

poetry run uvicorn app.main:app --reload --port XXXXXWhere XXXXX is a number generated using the command below. In a bash cell, run the following code.

port21650 # your number may be different!

|

You must run this in a bash cell. This bash script lives in the |

Then, given your available port number, run the following from your terminal tab.

module use /scratch/brown/kamstut/tdm/opt/modulefiles

module load poetry/1.1.10

cd $HOME/f2021-stat39000-project8

poetry run uvicorn app.main:app --reload --port 21650 # if your port was 1111 you'd replace 21650 with 1111|

Replace 21650 with the port number from your |

Once successful, you should see text similar to the following.

INFO: Will watch for changes in these directories: ['$HOME/f2021-stat39000-project8'] INFO: Uvicorn running on http://127.0.0.1:8000 (Press CTRL+C to quit) INFO: Started reloader process [94978] using watchgod INFO: Started server process [94997] INFO: Waiting for application startup. INFO: Application startup complete.

Then, to see the API, or the responses, normally you could just navigate to localhost:21650, and enter the URLs there. By default, the browser will GET those responses. Since our compute environment is a little bit more complicated, we will limit GET’ing our responses using the requests package.

Run the following in a cell.

import requests

response = requests.get("http://localhost:21650")

print(response.json())You should be presented with an extremely boring result — a simple "hello world". Yay! You are running an API and even made a GET request to that API using the requests package. While this may or may not seem too cool to you, it is pretty awesome! I hope these next few projects will be fun for you!

|

Please send any feedback you may have to [email protected]/[email protected]/[email protected]. This is the first time we are testing out these project ideas, so any feedback — positive or negative — is welcome! I’ve already made a lot of notes to make some of the earlier projects less time consuming. We ultimately want to make these projects fun, give you some exposure to cool techniques used in industry, and hopefully make you a better programmer/statistician/nurse/whathaveyou. With that being said, I have definitely missed the mark many times, and your feedback helps a lot. |

-

Code used to solve this problem.

-

Output from running the code.

Question 2

Great! Now, you have our API running on Brown. Now its time to learn about what the heck an API is. There are a lot of different types of APIs. The most common used today are RESTful APIs (what we will be focusing on, probably the most popular), graphQL APIs, and gRPC APIs.

This is a decent article highlighting the various types of APIs (feel free to skip the antiquated SOAP). Summarize the 3 mentioned APIs (RESTful, gRPC, and graphQL) in 1-2 sentences, and write at least 1 pro and 1 con of each.

As I mentioned before, it makes the most sense to focus on RESTful APIs at this point in time, however, gRPC and graphQL have some serious advantages that make them very popular in industry. It is likely you will run into some of these in your future work.

-

Code used to solve this problem.

-

Output from running the code.

Question 3

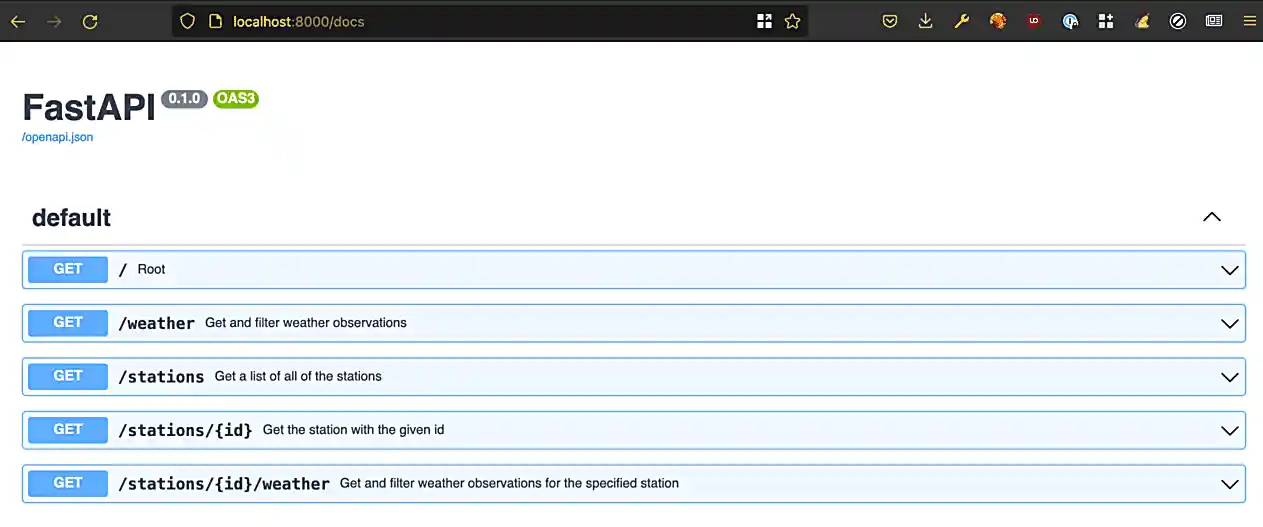

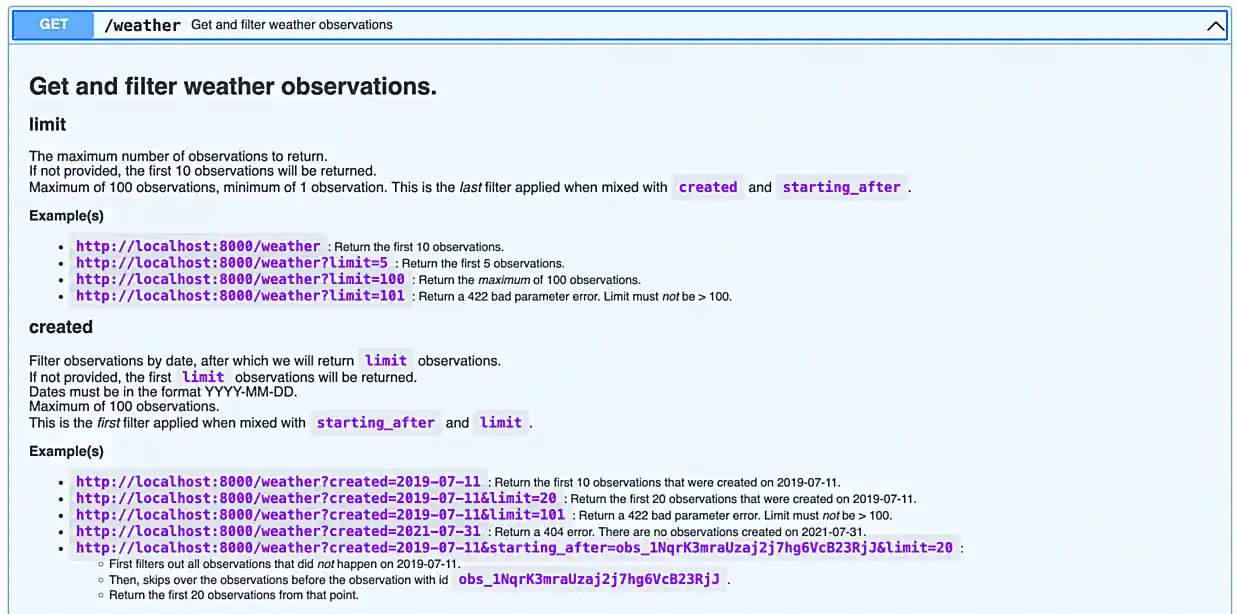

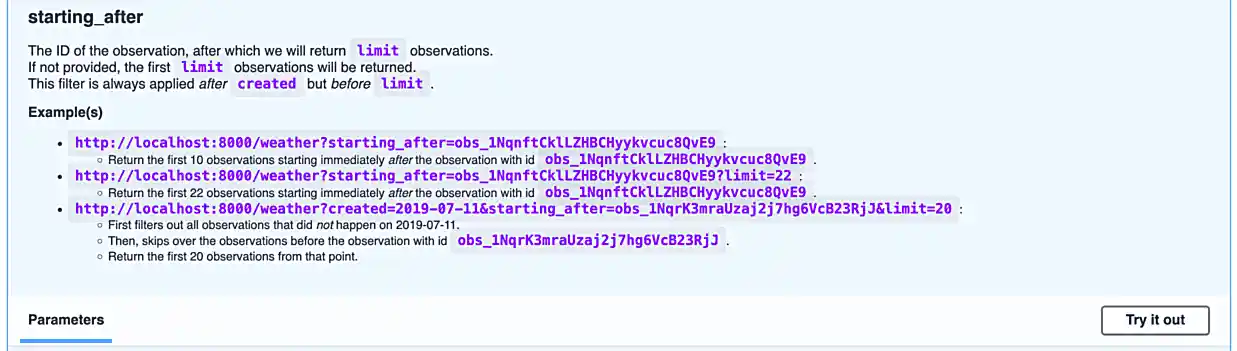

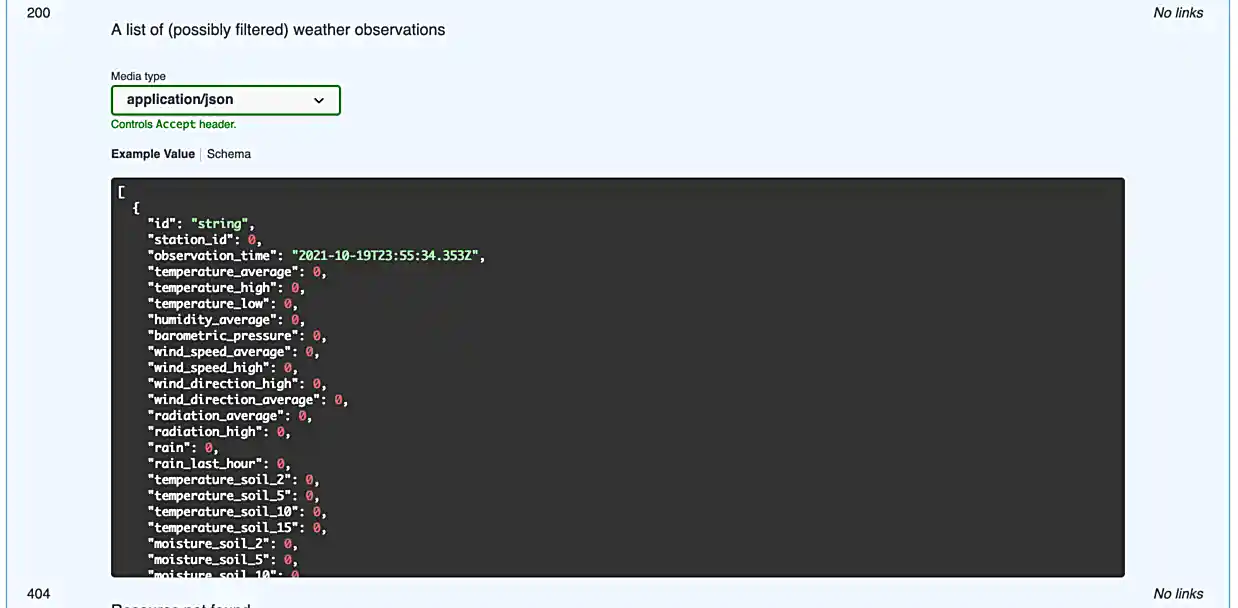

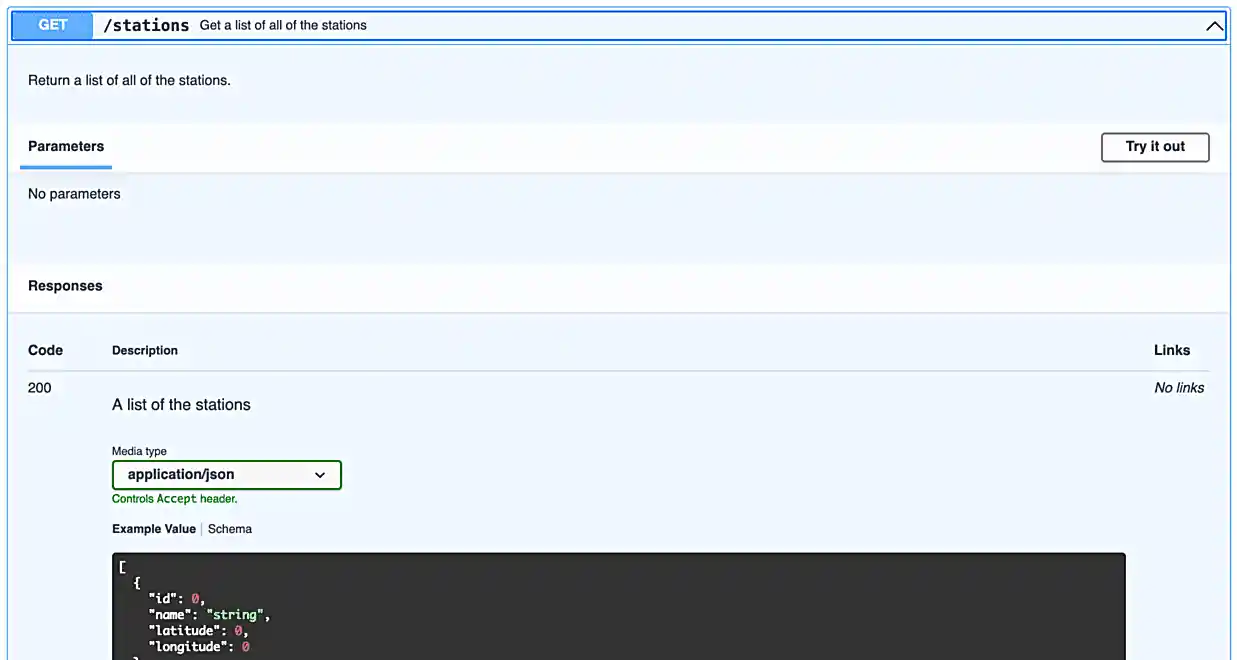

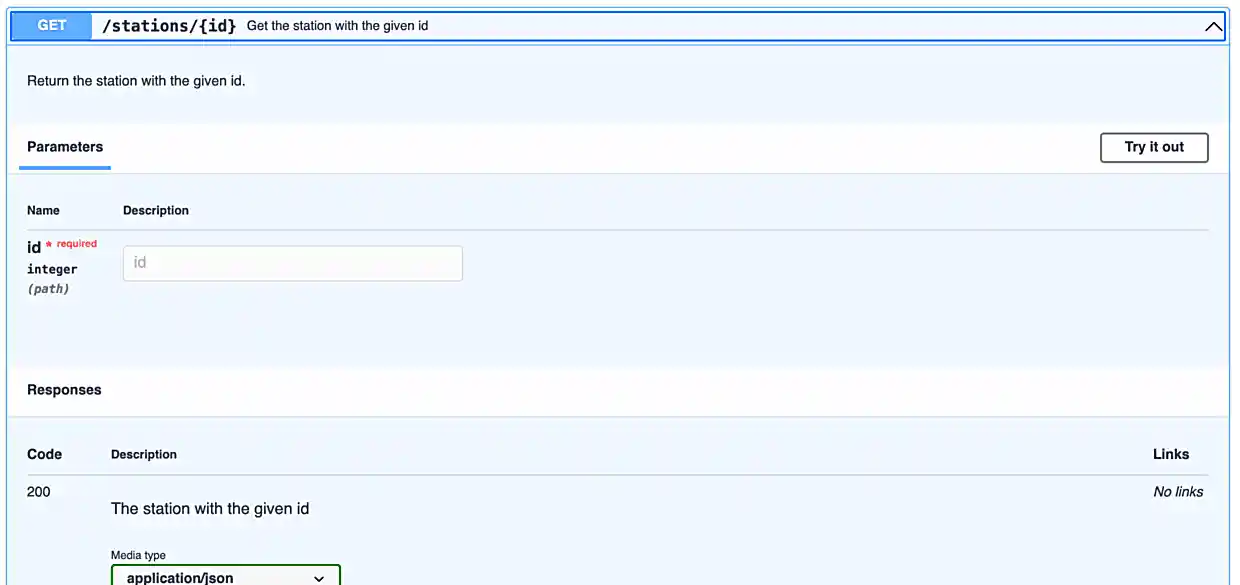

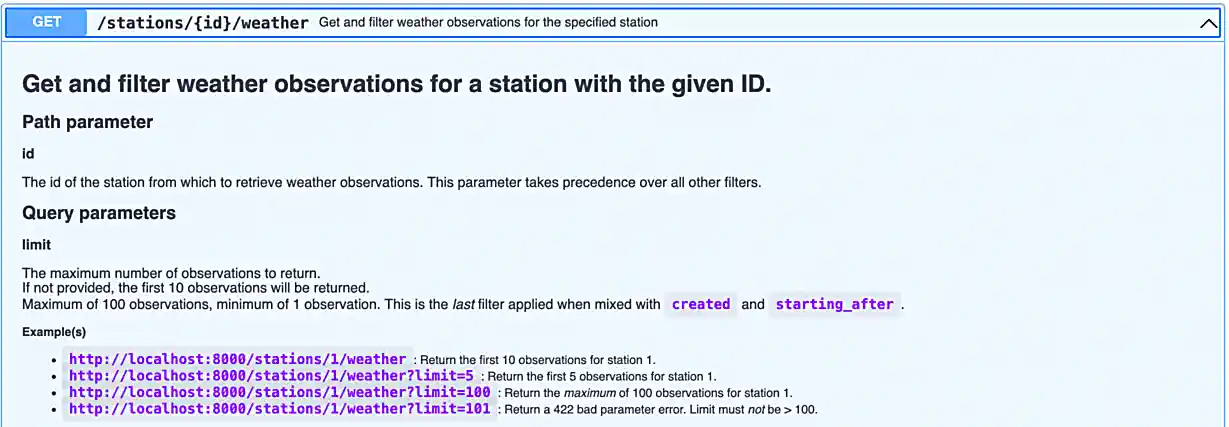

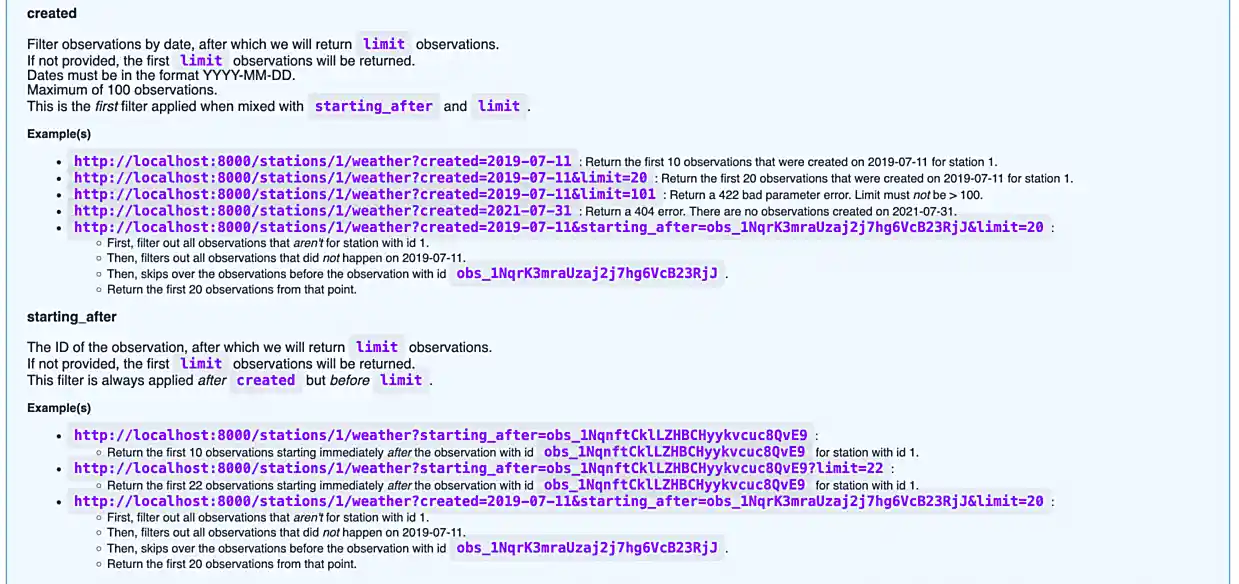

Since it is not so straightforward to pull up the automatically generated, interactive, API documentation, we’ve provided a screenshot below.

Awesome! There are some pretty detailed docs that we incorporated.

Let’s make a request to our API. Once we make a request to our API, we will receive a response back. The main components of a request are:

-

The method (GET, POST, PUT, DELETE, etc.)

-

The path (the URL path)

-

The headers (the HTTP headers)

-

The body (the data that is sent in the request)

Thats it!

The only method we will talk about in this project is the GET method. If you want a list of methods, simply Google "HTTP methods" and you should find a list of all the methods.

The GET method is the same method that browsers primarily utilize when they navigate to a website. They GET the website content.

The path starts after the URL. In our case, the path was /docs/ to get the docs! The path highlights the resource we are trying to access.

The headers are sent with the request and can be used for a wide variety of things. For example, in the next question, we will use a header to authenticate with the real WHIN API and make a request.

Finally, the body is the data that is sent with the request. In our case, we will not be sending any data with our request, instead, we will be receiving data in the body of our response.

To make a response to our API, we can use the requests package. Run the following in a Python cell.

import requests

response = requests.get('http://localhost:21650/stations/')response will then contain your — response! If you look over in your terminal tab, you will see that our API logged the request we made.

The response will contain a status code. You can see a list of status codes, and what they mean here.

To get the status code from your response variable, try the following.

response.status_codeRun the following to get a list of the methods and attributes available to you with the response object.

dir(response)You can see a lot — this is a useful "trick" in python. Alternatively, like most dunder methods, you could also run the following.

response.__dir__()This is the same as:

dir(response)Okay, great!

You can get the headers like this:

response.headersYou can get the pure text of the response like this:

response.textFinally, to the the JSON formatted body of the response, you can use the json method, which will return a list of dicts containing the data!

response.json() # the open and closed parenthesis are important. `json()` is a method not an attribute (like `.text`), so the parentheses are important.As you may have ascertained, the endpoint, localhost:21650/stations/, will return a list of station objects — very cool!

In another tab in your regular browser running on your local machine, navigate to the official WHIN api docs (you may need to login). Follow the directions at the beginning of this project to be able to authenticate with the WHIN API (questions 1 and 2).

Next, make sure you followed the instructions in question (2) from this project and that your .env file now contains something like:

DATABASE_PATH=/depot/datamine/data/whin/whin.db MY_BEARER_TOKEN=eyJhbGciOiJSUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJ1c2VyIjp7ImlkIjo5LCJkaXsdgw3ret234gBbXN0dXR6IiwiYWNjb3VudF90eXBlIjoiZWR1Y2F0aW9uIn0sImlhdCI6MTYzNDgyMzUyOSwibmJmIjoxNjM0ODIzNTI5LCJleHAiOjE2NjYzNTk1MjksImlzcyI6Imh0dHBzOi8vd2hpbi5vcmcifQ.LASER2vFONRhkdrPtEwca0eGxCtbjJ4Btaurgerg7l27z_Rwqhy1gghdFpscLFkFzfVw7VUdV_hlJ1rzmHi8i75hcLEUL18T76kdY82yb7Q8b_YTB32iQnJDP3uVQP5sQWs5mv8HcEj6W7jNX5HQe-iItzBXVAcMBUmR0SK9Pt2JRmCbuHpM242JJqwBvEMZw1mjNWGs70c595QqyxaUtgrSSmMBbZQeaN21U9EuSEjUKBRgtjl-9t-IhLkLVNo008Vq4v-sA

If you are having a hard time adding another line to your .env file, you can also run the following in a bash cell to append the line to your .env file. Make sure you replace the token with your token.

echo "eyJhbGciOiJSUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJ1c2VyIjp7ImlkIjo5LCJkaXsdgw3ret234gBbXN0dXR6IiwiYWNjb3VudF90eXBlIjoiZWR1Y2F0aW9uIn0sImlhdCI6MTYzNDgyMzUyOSwibmJmIjoxNjM0ODIzNTI5LCJleHAiOjE2NjYzNTk1MjksImlzcyI6Imh0dHBzOi8vd2hpbi5vcmcifQ.LASER2vFONRhkdrPtEwca0eGxCtbjJ4Btaurgerg7l27z_Rwqhy1gghdFpscLFkFzfVw7VUdV_hlJ1rzmHi8i75hcLEUL18T76kdY82yb7Q8b_YTB32iQnJDP3uVQP5sQWs5mv8HcEj6W7jNX5HQe-iItzBXVAcMBUmR0SK9Pt2JRmCbuHpM242JJqwBvEMZw1mjNWGs70c595QqyxaUtgrSSmMBbZQeaN21U9EuSEjUKBRgtjl-9t-IhLkLVNo008Vq4v-sA" >> $HOME/f2021-stat39000-project08/.env|

You must replace the "MY_BEARER_TOKEN" with your token from this page. |

When configured, make the following request.

import requests

import os

from dotenv import load_dotenv

load_dotenv(os.getenv("HOME")+"/f2021-stat39000-project8/.env")

my_headers = {"Authorization": f"Bearer {os.getenv('MY_BEARER_TOKEN')}"}

response = requests.get("https://data.whin.org/api/weather/stations", headers = my_headers)

print(response.json())You’ll find that the responses are very similar — but of course, ours is just a sample of theirs.

Notice that the response is pretty long, but it is a list of dictionaries, so we can easily print the first 5 values only, like this.

print(response.json()[:5])-

Code used to solve this problem.

-

Output from running the code.

Question 4

You’ve successfully made a request to both our API (which you are running in the terminal tab), and the WHIN API — very cool!

Read the documentation provided for our API in the screenshots in question (3), and make a request with a query parameter. A query parameter is a parameter that is added to the URL itself. Query parameters are added to the end of a URL. They start with a "?", have key, value pairs separated by "=", and many can be strung together using "&" to separate them. For example.

http://localhost:21650/some_endpoint?queryparam1key=queryparam1value&queryparam2key=queryparam2value

Here, we have 2 query parameters, queryparam1key and queryparam2key, and their values are queryparam1value and queryparam2value, respectively.

In our API, there are a few endpoints that give you optional query parameters (see the images in question (3)) — use the requests library to test it out and make a request involving at least 1 query parameter with any of the endpoints we provide with our API.

Now, try and replicate the request using the original WHIN API — were you able to fully replicate it?

|

When we ask "were you able to fully replicate it", all we want to know is if the WHIN API happens to provide the same functionality. |

The APIs are pretty different, and provide different functionalities. APIs are not the same, and depending on the purpose of you API, you may build it differently! Very cool!

-

Code used to solve this problem.

-

Output from running the code.

Question 5

Make a new request to our API, and use at least 2 query parameters in your request — do the results make sense based on what you’ve read on the docs? Why or why not?

In websites, a common feature is pagination — the ability to page through lots of results, one page at a time. Often times this will look like a "Next" and "Previous" button in a webpage. Which of the query parameters would be useful for pagination in our API and why?

Finally, make a new request to the original WHIN API. Specifically, try and test out the very cool current-conditions endpoint that allows you to zone in on stations near a certain latitude and longitude location. Can you replicate this with our API, or do we not have that capability baked in?

-

Code used to solve this problem.

-

Output from running the code.

|

Please make sure to double check that your submission is complete, and contains all of your code and output before submitting. If you are on a spotty internet connection, it is recommended to download your submission after submitting it to make sure what you think you submitted, was what you actually submitted. |